Securing our next drop: Millions are being invested in producing and conveying water. Insight looks at Singapore's quest for a robust supply.

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

On a stretch of reclaimed land in Tuas, a water factory is taking shape. Singapore's third desalination plant, expected to be ready later this year, is one of several infrastructure projects in the pipeline to ensure a nation surrounded by water has enough to meet its needs.

At two older plants nearby, sea water is already filtered and passed through membranes to remove dissolved salts and minerals, as part of a process to get water fit to drink.

Singapore's fourth national tap - desalinated water - is part of a long, and often little-heard, story of this nation's quest for self-sufficiency in man's most valuable resource.

Tap one: Catchment areas were expanded, and new storm drains and reservoirs built over the years.

Tap two: Imported water, made possible through two agreements with Malaysia that Singapore leaders made sure were guaranteed in the 1965 Separation Agreement.

Tap three: NEWater - high-grade recycled water - launched in 2003 with two plants in Bedok and Kranji. Three more have since opened.

Tap four was turned on in 2005, with the opening of SingSpring desalination plant in Tuas made possible by advances in technology.

Today, NEWater meets up to 40 per cent of Singapore's water demand and desalination 25 per cent.

And plans are under way to boost capacity so both meet 55 per cent and 30 per cent of water needs respectively by 2060, before the second water agreement expires.

But the cost of operating and maintaining the water system has risen over the years, prompting the Government to review the price of water - and raise it by 30 per cent over two phases, this July and next.

It is the first price hike in 17 years.

The previous hike, phased in from 1997 to 2000, saw tariffs go up by 20 per cent to 100 per cent on a scale depending on usage.

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

On a stretch of reclaimed land in Tuas, a water factory is taking shape. Singapore's third desalination plant, expected to be ready later this year, is one of several infrastructure projects in the pipeline to ensure a nation surrounded by water has enough to meet its needs.

At two older plants nearby, sea water is already filtered and passed through membranes to remove dissolved salts and minerals, as part of a process to get water fit to drink.

Singapore's fourth national tap - desalinated water - is part of a long, and often little-heard, story of this nation's quest for self-sufficiency in man's most valuable resource.

Tap one: Catchment areas were expanded, and new storm drains and reservoirs built over the years.

Tap two: Imported water, made possible through two agreements with Malaysia that Singapore leaders made sure were guaranteed in the 1965 Separation Agreement.

Tap three: NEWater - high-grade recycled water - launched in 2003 with two plants in Bedok and Kranji. Three more have since opened.

Tap four was turned on in 2005, with the opening of SingSpring desalination plant in Tuas made possible by advances in technology.

Today, NEWater meets up to 40 per cent of Singapore's water demand and desalination 25 per cent.

And plans are under way to boost capacity so both meet 55 per cent and 30 per cent of water needs respectively by 2060, before the second water agreement expires.

But the cost of operating and maintaining the water system has risen over the years, prompting the Government to review the price of water - and raise it by 30 per cent over two phases, this July and next.

It is the first price hike in 17 years.

The previous hike, phased in from 1997 to 2000, saw tariffs go up by 20 per cent to 100 per cent on a scale depending on usage.

Costs have gone up sharply since then. Last month, national water agency PUB said it cost about $500 million to run the system in 2000. By 2015, this had risen to $1.3 billion. This includes collecting used water, treating water, producing NEWater and desalination, as well as maintaining water pipelines.

WHAT PRICE, WATER?

As Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat and Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli reminded Parliament this month, the cornerstone of Singapore's water policy is the pricing of water on sound economic principles to reflect what is called its Long Run Marginal Cost (LRMC).

WHAT PRICE, WATER?

As Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat and Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli reminded Parliament this month, the cornerstone of Singapore's water policy is the pricing of water on sound economic principles to reflect what is called its Long Run Marginal Cost (LRMC).

This reflects the cost of supplying the next available drop of water, which is likely to come from NEWater and desalination plants, and enabling investments in such plants.

Mr Masagos noted the first-year price of the first desalination plant, SingSpring, which opened in 2005, was 78 cents per cubic m. By comparison, the first-year price of the latest plant in Marina East, set to open in 2020, is $1.08 per cubic m - an increase of some 40 per cent.

Understandably, the price hike generated much discussion on the ground, prompting ministers to point out that, in reality, most businesses will see a rise of less than $1 a day, and for most households, a jump of less than $12 a month.

And at the start of a month-long water conservation campaign, Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean pointed out that a 330ml bottle of water costing $1 from a supermarket will pay for 1,000 bottles of clean water from the tap after the full price rise.

It is a price comparable to that in major cities in developed countries with large rivers to draw from. It is also a price that makes possible considerable investments in the future.

The years from 2000 to 2015 saw $7 billion invested in water infrastructure - or $430 million a year. PUB expects this to almost double to $800 million every year from this year to 2021, to fund major investments in strengthening the third and fourth taps, and build and repair pipes and pumps. There are also higher costs of manpower, materials and chemicals, and more difficult and expensive developments needed, such as having to dig deeper underground to lay pipelines.

Less noticed but equally crucial to water management are several intangible aspects of Singapore's approach to water.

The years from 2000 to 2015 saw $7 billion invested in water infrastructure - or $430 million a year. PUB expects this to almost double to $800 million every year from this year to 2021, to fund major investments in strengthening the third and fourth taps, and build and repair pipes and pumps. There are also higher costs of manpower, materials and chemicals, and more difficult and expensive developments needed, such as having to dig deeper underground to lay pipelines.

Less noticed but equally crucial to water management are several intangible aspects of Singapore's approach to water.

One is minimising leakage. Only 5 per cent of treated water in Singapore is lost through leakages - a figure bested by Tokyo but ahead of the United States and Hong Kong.

Some developing cities can lose as much as 60 per cent of their water through leaks, notes water expert Asit Biswas at the National University of Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Another not-so-visible reward of Singapore's meticulous water planning is that two-thirds of the country serves as a catchment area for drinking water supply, among the highest in the world.

Another not-so-visible reward of Singapore's meticulous water planning is that two-thirds of the country serves as a catchment area for drinking water supply, among the highest in the world.

Furthermore, the price of water enables not just the production and delivery of potable water, but also the treatment of sewage and industrial waste water so it can safely go back into the environment.

One fact not often appreciated is that Singapore has separate systems for drainage and sewage, a more efficient set-up than a system in which everything flows into sewage, such as in London.

PUB said sudden surges of water caused by stormwater flowing through a combined system will reduce the effectiveness of the microorganisms used for biological treatment in water reclamation plants.

A Deep Tunnel Sewerage System is also being built to collect, treat, reclaim and dispose of used water from industries, homes and businesses, that will feed into a water reclamation plant and NEWater factory, and should be ready by 2025.

This determination to make every last drop of water matter has seen other countries wanting to learn from Singapore's experience, and spawned opportunities for home-grown water companies.

In California, water managers are adapting a technology refined in Singapore - the membrane bioreactor - to treat industrial waste water and use the treated water to directly replenish the water-stressed state's freshwater aquifers instead of discharging it into the sea.

They are doing this with the help of international environmental engineering company CH2M, which is designing the new Tuas Water Reclamation Plant. The membrane bioreactor combines filtration with biological breakdown of organic matter by microorganisms.

Said Mr Peter Nicol, CH2M's senior vice-president and global director of water: "Singapore has identified the areas it would like to see improvement in, and put challenges out to the private sector to come and work with them aggressively on piloting technologies full-scale. It then shares that information with the global water market."

Even as Singapore builds a robust, diversified water supply across its national taps, a key complementary strategy has been to drive home the importance of conserving water. Public education has seen results: Between 2003 and 2015, households cut their water use per person per day from 165 litres to 151 litres. The PUB's long-term goal is to see this lowered to 140 litres by 2030.

Observers say there are several cities from whose books Singapore could take a leaf from in the "softer" side of water conservation. In Sao Paulo, which experienced a drought from 2014 to 2015, water use fell 30 per cent in a year, helped by discounts given to people who reduced consumption. Prof Biswas says Singapore could benefit from such financial incentives for reducing water use. "Sao Paulo is growing much faster than Singapore," he says. "The government went to the people saying: 'Look, we cannot solve the problem until you change your behaviour.' People realised water was becoming scarce and they had to do something," he said.

Namibia's capital Windhoek has another lesson. Situated in an arid climate with frequent droughts, it has been treating its waste water and putting it directly back into taps, because it has no other choice.

CHANGING BEHAVIOUR

There are other ways to encourage people to value water more and use less of it, such as having multiple tiers in water charging.

Singapore has a two-tier system of domestic potable water tariffs, with one price per cubic m for the first 40 cubic m and a higher price for anything beyond. PUB says the 40 cubic m limit meets most needs as 94 per cent of households consume less than that volume every month.

Therein lies the problem, says Prof Biswas, as most people won't feel the pain of the more expensive tier. He feels the first tier should be much lower in consumption, closer to the reasonable water use expected of an average household, and usage beyond that split into three more tiers to penalise high water usage. "You can use more water, but you have to pay more for it. Society does not owe you as much water as you want," he says.

However, PUB said properly multi-tiering the water tariff would require a complicated system to accurately determine the number of people per household and how it changes over time. It would also mean applying different thresholds for different household sizes and this would raise costs, it added.

One thing is clear: Singapore should not go the way of others and underprice water. Observers cite how India, for instance, has difficulty developing water infrastructure, or Qatar has a hard time cutting consumption as water is free for locals.

Mr Subbu Kanakasabapathy, CH2M's regional managing director for the Asia-Pacific, says this has resulted in the poor paying more for water in India than if it were priced properly, because they are forced to buy water at a high price from private water trucks.

The unreliable water supply also compromises health.

Which is why Prof Biswas feels if Singapore adds a fifth national tap, it should be a very different kind of tap from the first four - to reduce demand for water, rather than increasing supply as civilisations have been doing for centuries. It can be done, as others have shown.

The World Health Organisation says only 50 to 100 litres of water are needed per person per day for basic needs. If Singapore cuts its per capita daily consumption from the current 148 litres to 100 litres, it would save 240 million litres every day for a population of five million.

"Technology is not going to solve our problems as it did in the past. The next breakthrough has to come from the behavioural sciences. The water industry needs more psychologists and behavioural economists," said Prof Biswas. "We have to try everything."

In a primer on water in the Singapore Chronicles series published last year, PUB chairman Tan Gee Paw notes that two big challenges of water management Singapore is likely to face in future are climate change and complacency.

"In less than a lifetime, Singapore's efforts at water management have come a long way," he wrote. "It is the enduring legacy of a small, dry island that such efforts remain unceasing, unrelenting and ever more vigilant."

The attention water has had in the headlines in recent weeks is thus a reminder that Singapore's water journey is far from over, even as it works towards self-sufficiency before the end of the water agreement in 2061.

A Deep Tunnel Sewerage System is also being built to collect, treat, reclaim and dispose of used water from industries, homes and businesses, that will feed into a water reclamation plant and NEWater factory, and should be ready by 2025.

This determination to make every last drop of water matter has seen other countries wanting to learn from Singapore's experience, and spawned opportunities for home-grown water companies.

In California, water managers are adapting a technology refined in Singapore - the membrane bioreactor - to treat industrial waste water and use the treated water to directly replenish the water-stressed state's freshwater aquifers instead of discharging it into the sea.

They are doing this with the help of international environmental engineering company CH2M, which is designing the new Tuas Water Reclamation Plant. The membrane bioreactor combines filtration with biological breakdown of organic matter by microorganisms.

Said Mr Peter Nicol, CH2M's senior vice-president and global director of water: "Singapore has identified the areas it would like to see improvement in, and put challenges out to the private sector to come and work with them aggressively on piloting technologies full-scale. It then shares that information with the global water market."

Even as Singapore builds a robust, diversified water supply across its national taps, a key complementary strategy has been to drive home the importance of conserving water. Public education has seen results: Between 2003 and 2015, households cut their water use per person per day from 165 litres to 151 litres. The PUB's long-term goal is to see this lowered to 140 litres by 2030.

Observers say there are several cities from whose books Singapore could take a leaf from in the "softer" side of water conservation. In Sao Paulo, which experienced a drought from 2014 to 2015, water use fell 30 per cent in a year, helped by discounts given to people who reduced consumption. Prof Biswas says Singapore could benefit from such financial incentives for reducing water use. "Sao Paulo is growing much faster than Singapore," he says. "The government went to the people saying: 'Look, we cannot solve the problem until you change your behaviour.' People realised water was becoming scarce and they had to do something," he said.

Namibia's capital Windhoek has another lesson. Situated in an arid climate with frequent droughts, it has been treating its waste water and putting it directly back into taps, because it has no other choice.

CHANGING BEHAVIOUR

There are other ways to encourage people to value water more and use less of it, such as having multiple tiers in water charging.

Singapore has a two-tier system of domestic potable water tariffs, with one price per cubic m for the first 40 cubic m and a higher price for anything beyond. PUB says the 40 cubic m limit meets most needs as 94 per cent of households consume less than that volume every month.

Therein lies the problem, says Prof Biswas, as most people won't feel the pain of the more expensive tier. He feels the first tier should be much lower in consumption, closer to the reasonable water use expected of an average household, and usage beyond that split into three more tiers to penalise high water usage. "You can use more water, but you have to pay more for it. Society does not owe you as much water as you want," he says.

However, PUB said properly multi-tiering the water tariff would require a complicated system to accurately determine the number of people per household and how it changes over time. It would also mean applying different thresholds for different household sizes and this would raise costs, it added.

One thing is clear: Singapore should not go the way of others and underprice water. Observers cite how India, for instance, has difficulty developing water infrastructure, or Qatar has a hard time cutting consumption as water is free for locals.

Mr Subbu Kanakasabapathy, CH2M's regional managing director for the Asia-Pacific, says this has resulted in the poor paying more for water in India than if it were priced properly, because they are forced to buy water at a high price from private water trucks.

The unreliable water supply also compromises health.

Which is why Prof Biswas feels if Singapore adds a fifth national tap, it should be a very different kind of tap from the first four - to reduce demand for water, rather than increasing supply as civilisations have been doing for centuries. It can be done, as others have shown.

The World Health Organisation says only 50 to 100 litres of water are needed per person per day for basic needs. If Singapore cuts its per capita daily consumption from the current 148 litres to 100 litres, it would save 240 million litres every day for a population of five million.

"Technology is not going to solve our problems as it did in the past. The next breakthrough has to come from the behavioural sciences. The water industry needs more psychologists and behavioural economists," said Prof Biswas. "We have to try everything."

In a primer on water in the Singapore Chronicles series published last year, PUB chairman Tan Gee Paw notes that two big challenges of water management Singapore is likely to face in future are climate change and complacency.

"In less than a lifetime, Singapore's efforts at water management have come a long way," he wrote. "It is the enduring legacy of a small, dry island that such efforts remain unceasing, unrelenting and ever more vigilant."

The attention water has had in the headlines in recent weeks is thus a reminder that Singapore's water journey is far from over, even as it works towards self-sufficiency before the end of the water agreement in 2061.

Feeling the heat after drying up of 'water is precious' message

There can be no let-up in long struggle to break out of the water vulnerability Singaporeans once bemoaned

By Warren Fernandez, Editor, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

"Potong, potong, potong."

Led by then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, Umno hotheads chanted this cry to cut, cut, cut water supplies to Singapore at a rally in Johor Baru, right on the Republic's doorstep.

That was in 1998.

Here's how a neutral observer reported the incident in Britain's Independent newspaper on Aug 8 that year: "Gripped by a severe economic recession, mortified by a bungled opening of the new international airport, confronted by mounting anger over water shortages in the capital, and facing deep divisions in the ruling party, Malaysia's prime minister badly needs an issue to unite the nation.

"Fortunately for him, the issue lies close at hand and can always be relied upon to stir passion in Malaysia. That issue is Singapore."

Malaysia's "abrasive leader", the paper continued, had told crowds at the rally that "Malaysia's nature is to be good to all... but don't take for granted our good nature".

The crowd responded eagerly with cries of "cut, cut, cut", meaning they wanted Malaysia to cut off the water supplies on which Singapore is totally dependent for its survival.

Singapore's response? A Ministry of Foreign Affairs official was quoted as saying laconically: "We have lived with this for many years."

Indeed we had. So much so that it began to grate, and many Singaporeans began to yearn for something to be done to break out of the country's heavy reliance on its neighbour for such a critical resource.

At the time, I wrote a column on the issue, which was headlined "Big thirst for water solution", arguing that the day had come for the Government to take the plunge and invest heavily in building desalination plants.

It read: "Cost, it seems, rather than the lack of know-how, is the reason the authorities chose to proceed with caution. Apart from the initial investment, it is estimated that the cost of producing a cubic metre of desalinated water is $3 to $3.50, about seven or eight times the cost of treating freshwater now.

"Assuming that Singapore's water demand stays at the current 270 million gallons per day (mgd) and domestic supply remains at 150 mgd, four of such distillation plants will be needed to make up the remaining 120 mgd. This would cost a total of $4 billion.

There can be no let-up in long struggle to break out of the water vulnerability Singaporeans once bemoaned

By Warren Fernandez, Editor, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

"Potong, potong, potong."

Led by then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, Umno hotheads chanted this cry to cut, cut, cut water supplies to Singapore at a rally in Johor Baru, right on the Republic's doorstep.

That was in 1998.

Here's how a neutral observer reported the incident in Britain's Independent newspaper on Aug 8 that year: "Gripped by a severe economic recession, mortified by a bungled opening of the new international airport, confronted by mounting anger over water shortages in the capital, and facing deep divisions in the ruling party, Malaysia's prime minister badly needs an issue to unite the nation.

"Fortunately for him, the issue lies close at hand and can always be relied upon to stir passion in Malaysia. That issue is Singapore."

Malaysia's "abrasive leader", the paper continued, had told crowds at the rally that "Malaysia's nature is to be good to all... but don't take for granted our good nature".

The crowd responded eagerly with cries of "cut, cut, cut", meaning they wanted Malaysia to cut off the water supplies on which Singapore is totally dependent for its survival.

Singapore's response? A Ministry of Foreign Affairs official was quoted as saying laconically: "We have lived with this for many years."

Indeed we had. So much so that it began to grate, and many Singaporeans began to yearn for something to be done to break out of the country's heavy reliance on its neighbour for such a critical resource.

At the time, I wrote a column on the issue, which was headlined "Big thirst for water solution", arguing that the day had come for the Government to take the plunge and invest heavily in building desalination plants.

It read: "Cost, it seems, rather than the lack of know-how, is the reason the authorities chose to proceed with caution. Apart from the initial investment, it is estimated that the cost of producing a cubic metre of desalinated water is $3 to $3.50, about seven or eight times the cost of treating freshwater now.

"Assuming that Singapore's water demand stays at the current 270 million gallons per day (mgd) and domestic supply remains at 150 mgd, four of such distillation plants will be needed to make up the remaining 120 mgd. This would cost a total of $4 billion.

"Yet, this is less than the $5 billion being spent to build the North-East MRT line or the planned underground road system, and a quarter of the $20 billion set aside for the Housing Board's Main Upgrading Programme to spruce up older HDB estates.

"Indeed, if Singapore could invest millions to develop and pioneer technology for its Electronic Road Pricing system to ensure that highways in the land-scarce country remain unclogged, why baulk at spending to develop the means to overcome its lack of an even more critical resource - water?"

"Indeed, if Singapore could invest millions to develop and pioneer technology for its Electronic Road Pricing system to ensure that highways in the land-scarce country remain unclogged, why baulk at spending to develop the means to overcome its lack of an even more critical resource - water?"

Many readers seemed to agree, going by the number who wrote in to our Forum pages, some suggesting solutions and others, invoking that famous John F. Kennedy line, insisting that the country stood ready to "pay any price, or bear any burden" to free itself from having to live with the unremitting threats from politicians up north.

Thankfully, Singapore pressed ahead, not only with desalination - the first plant to purify sea water was embarked on soon afterwards and completed in 2005 - but also by harnessing the technology to reclaim used water in 2003.

The latter, dubbed NEWater, proved to be a trump card in the Republic's interminable negotiations with Malaysia for new sources of water to meet Singapore's future needs.

Thankfully, Singapore pressed ahead, not only with desalination - the first plant to purify sea water was embarked on soon afterwards and completed in 2005 - but also by harnessing the technology to reclaim used water in 2003.

The latter, dubbed NEWater, proved to be a trump card in the Republic's interminable negotiations with Malaysia for new sources of water to meet Singapore's future needs.

Indeed, as my colleague Dominic Nathan wrote in this newspaper in 2003: "Although PUB has never revealed the price of NEWater, it has said that it is 50 to 60 per cent cheaper than desalted water. This means that if Malaysia is serious about wanting to return to the negotiating table, it will have to do better than Dr Mahathir's March 4 offer of about RM10 per thousand gallons for treated water, or around $1 per cubic m.

"Singapore's cards are now on the table. And if Malaysian leaders were under the impression that the gamble on NEWater was a bluff, they now know that it is the ace in Singapore's royal flush."

In other words, through sheer wit and will, Singapore had not only shaken off its water vulnerability but turned adversity to advantage through the development of its water technology. You can read more on this amazing water journey in our Insight special on water on pages B4 to B6.

So, what happened? How did we go from the high level of public consciousness on the water issue, and a national eagerness to tackle it decisively in the late 1990s, to the present angst and anger over the impending water price hike?

Indeed, it might be asked, why were prices left untouched for 17 years, even as demand for the precious resource continued to shoot up, and with it, the investments needed to prevent the hard- earned sense of water security from drying up.

Why did we let up on efforts to keep drumming home the "water is a precious, strategic resource" message, including through the use of proper pricing to reflect its value?

To be fair, political leaders did touch on this from time to time, posting photos of declining water levels in Johor's Linggui reservoir online and warning about the impact this might have on Singapore. But these efforts, alas, failed to make much of a splash.

Perhaps there were other more pressing challenges - the Sars crisis of 2003, the 2008 financial meltdown, the 2011 General Election setback for the ruling party, the bust-up over immigration in 2013 - which focused minds elsewhere, and made any notion of raising water prices seem foolhardy?

Why did we let up on efforts to keep drumming home the "water is a precious, strategic resource" message, including through the use of proper pricing to reflect its value?

To be fair, political leaders did touch on this from time to time, posting photos of declining water levels in Johor's Linggui reservoir online and warning about the impact this might have on Singapore. But these efforts, alas, failed to make much of a splash.

Perhaps there were other more pressing challenges - the Sars crisis of 2003, the 2008 financial meltdown, the 2011 General Election setback for the ruling party, the bust-up over immigration in 2013 - which focused minds elsewhere, and made any notion of raising water prices seem foolhardy?

Or, did we grow complacent, falling for the rather over-hyped notion that the existential issue of dependence on Malaysia for water had been "solved" by Singaporean ingenuity.

Hopefully not, for that would have been delusional, as even with Singapore's much trumpeted "four taps" - rain, imported water, desalination and NEWater - the Republic remains dependent on Malaysia for the lion's share of our water supply. And that's not even mentioning the likely growth in future water demand or the need to prepare for 2061, when the second water pact with Malaysia runs out.

Indeed, even while water prices were kept constant since 2000, demand continued to surge, from 270 mgd in the late 1990s to 430 mgd today, with this expected to almost double by 2060.

And, as more of our water is likely to come from desalination and recycling, both highly energy-intensive, the overall cost of water will inevitably rise too.

So, most adult Singaporeans know that, like it or not, these costs will have to be borne, one way or the other - through tariffs or taxes - and the only mitigation possible is to ensure that the most well-off pay a bigger share, while those most in need are given the greatest help to cope with the cost.

Yet, who can blame the public for being perturbed by the sudden announcement of a hefty 30 per cent hike after the long hiatus in discussions about water pricing and conservation?

In contrast, recent weeks have seen a deluge of information on the billions that the authorities have been spending to build and maintain Singapore's water infrastructure over the years.

But, alas, coming as it did after public anger had flared up on the issue, has left officials swimming against the tide with what seemed to many like post-facto justifications.

Contrast this with the approach taken by Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat in signalling that taxes will have to rise as government spending continues to mount, or Transport Minister Khaw Boon Wan alluding to how public transport fares will eventually have to go up.

They have sounded the alarm early, promised wide consultation and begun the long process of getting the necessary buy-in from the public for these unpopular but inevitable moves.

There is indeed never a good time to raise the prices of essential services. But experience has shown that the way to minimise the angst is to give people as much information on the need for the increase up front, and where possible, spread out the rise in small doses over the years. Successive Cost Review Committees have said as much.

Beyond this, on an issue as sensitive as water, a constant drip-feed on the relentless struggle required to ensure sufficient supplies, both for today and tomorrow, is needed.

Doing so will help make clear to everyone that cries of "potong" simply cut no ice with Singaporeans - past or present - who remain resolved to do whatever it takes to secure this precious necessity.

Doing so will help make clear to everyone that cries of "potong" simply cut no ice with Singaporeans - past or present - who remain resolved to do whatever it takes to secure this precious necessity.

Singapore at the front line of water innovation

In its desire to boost water security, it has become a hub for tech tie-ups and exchanges

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

The so-called water industry is much more than about making money, because a clean and reliable water supply is vital not just to business but also mankind's survival.

For this reason, Singapore is at the front line of water innovation, becoming a hub for mutually beneficial technology collaborations and exchanges as it shores up its own water security.

"We're in that pivotal moment where we're building on data, robotics, smart manufacturing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage," Mr Subbu Kanakasabapathy, regional managing director for Asia Pacific at international environmental engineering company CH2M, tells Insight.

"The entire industry is changing. There is a beautiful fusion of physical, digital and biological knowledge."

Playing a key role in stimulating this exchange of ideas from multiple disciplines is the Singapore International Water Week, an annual convention started in 2008 where people and organisations from all over the world meet and share the latest ideas in water technology, management and education.

At present, there are 180 water companies in Singapore, and national water agency PUB has collaborated with more than 170 businesses, academic institutions or government agencies in just about every region of the world.

In terms of technology, Mr Kanakasabapathy says Singapore is moving towards a "water, energy and waste nexus" to increase water production while reducing energy consumption and waste generation.

In its desire to boost water security, it has become a hub for tech tie-ups and exchanges

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

The so-called water industry is much more than about making money, because a clean and reliable water supply is vital not just to business but also mankind's survival.

For this reason, Singapore is at the front line of water innovation, becoming a hub for mutually beneficial technology collaborations and exchanges as it shores up its own water security.

"We're in that pivotal moment where we're building on data, robotics, smart manufacturing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage," Mr Subbu Kanakasabapathy, regional managing director for Asia Pacific at international environmental engineering company CH2M, tells Insight.

"The entire industry is changing. There is a beautiful fusion of physical, digital and biological knowledge."

Playing a key role in stimulating this exchange of ideas from multiple disciplines is the Singapore International Water Week, an annual convention started in 2008 where people and organisations from all over the world meet and share the latest ideas in water technology, management and education.

At present, there are 180 water companies in Singapore, and national water agency PUB has collaborated with more than 170 businesses, academic institutions or government agencies in just about every region of the world.

In terms of technology, Mr Kanakasabapathy says Singapore is moving towards a "water, energy and waste nexus" to increase water production while reducing energy consumption and waste generation.

For example, from the breakdown of waterborne biodegradable material in water reclamation plants (WRPs), the PUB has been able to generate biogas, which powers one-quarter of the energy needed by WRPs in Singapore. It is now considering the possibility of adding food waste to the mix to increase the amount of biogas produced.

"The technology may have originated elsewhere, but Singapore is a fantastic test bed. Singapore has always reached out to other countries for cool technologies, and then said 'How do I embrace it, how do I optimise it'," says Mr Kanakasabapathy.

The benefits of global exchange are evident. Dutch water technology company PWN Technologies (PWNT) is fitting Japan-made ceramic membranes at Choa Chu Kang Water Works, a first in Singapore for treating reservoir water.

These membranes are more durable than conventional polymer membranes and can be used and cleaned at higher pressure to produce more water over a longer lifetime, with fewer costly plant breakdowns.

Although they cost much more up front than conventional membranes, they will result in lower costs in the long run, said PWNT, which is also exploring the use of ceramic membranes in desalination.

"The technology may have originated elsewhere, but Singapore is a fantastic test bed. Singapore has always reached out to other countries for cool technologies, and then said 'How do I embrace it, how do I optimise it'," says Mr Kanakasabapathy.

The benefits of global exchange are evident. Dutch water technology company PWN Technologies (PWNT) is fitting Japan-made ceramic membranes at Choa Chu Kang Water Works, a first in Singapore for treating reservoir water.

These membranes are more durable than conventional polymer membranes and can be used and cleaned at higher pressure to produce more water over a longer lifetime, with fewer costly plant breakdowns.

Although they cost much more up front than conventional membranes, they will result in lower costs in the long run, said PWNT, which is also exploring the use of ceramic membranes in desalination.

For smaller companies too, Singapore is a gateway to the global water playground.

De.mem, a Singapore-based small and medium-sized enterprise specialising in industrial waste water treatment, already has overseas offices in Australia and Vietnam, and is exploring potential markets in China and Germany.

A 2014 spinoff from Nanyang Technological University, De.mem counts among its clients multinational corporations in industries from food and beverage to oil and gas, a testament to how essential water is to other industries.

The company is developing a nano-filtration membrane - which has pores 10,000 times smaller than the diameter of human hair - that is cheaper to produce and can be used at much lower pressure than existing membranes of its kind. This saves energy and reduces system cost by up to 30 per cent. A pilot facility will be set up late next month.

De.mem chief executive Andreas Kroell says membrane technology, in general, has come a long way in achieving higher efficiency at lower cost, and sees it remaining the predominant technology in water treatment.

"Membrane technologies were developed over many decades," he says. "There haven't been overnight disruptions because technologies have to be tested and proven and that normally takes a while."

Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli told Parliament during the debate on the Budget this year: "Technologically, we have squeezed everything we can from the current water processing technology. It will take several more years to achieve the next breakthrough and bring it to a deployable scale."

An upcoming technology for desalination is electro-deionisation, which uses an electric field to "pull" salt from sea water. It consumes less energy than the current method of reverse osmosis, which relies on high pressure to push water molecules (not salt) through a membrane. PUB is testing the new technology in a small pilot plant in Tuas.

But while technology continues to improve the efficiency of water production, this does not mean the cost of water treatment will go down for the people treating it, says CH2M's senior vice-president and global director of water, Mr Peter Nicol.

There are many other factors in the equation that could make it more costly, such as the rising cost of power and the need to safeguard the system against increasingly temperamental weather, for instance.

PUB is already looking well ahead. For example, it is studying whether groundwater could be extracted for use on a regular basis, or during periods of drought. It is installing more monitoring wells and sensors to better understand Singapore's groundwater system.

The agency is also working with research institutions to look at novel, experimental ways of water production, such as using mangrove plants to convert sea water into freshwater.

But no matter the innovations to squeeze out every drop, water is a finite resource and Singapore's - and the world's - growing population would do well to use it judiciously.

Mr Jagadish CV, chief executive of semiconductor firm Systems on Silicon Manufacturing Company, says: "Technology and engineering will help recover more water, increase efficiency, even reduce usage... but to do that, the trigger is the mindset.

"It's the mindset of the common man, the mindset of the industry leaders, the mindset of the society - this is what's going to influence what we're going to do about it (water security)."

"It's the mindset of the common man, the mindset of the industry leaders, the mindset of the society - this is what's going to influence what we're going to do about it (water security)."

Centre monitors water supply and drainage flows

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

When a major fire broke out at a toxic waste management plant in Tuas last month, PUB engineers monitored the water supply to the hydrants to ensure firefighters had enough water to combat the blaze.

They also tracked drainage flows in the area, to check if any contaminated water from the fire was flowing to parts of the sea from which nearby desalination plants were drawing water.

They did so with a sophisticated real-time monitoring system in the national water agency's control centre, nestled somewhere in the Environment Building in Scotts Road.

The centre has 12 large screens and 16 smaller ones mounted on the wall, and many more on rows of consoles manned by engineers.

The screens display information on Singapore's water infrastructure in real-time - from detailed maps of water pipes and valves, to data on water pump pressure, flow rates and water quality. Set up in 2012 as part of PUB's Water Systems Unit, the control centre also draws information from other government agencies, like the National Environment Agency's weather radar.

When there is heavy rain and sensors in the canal warn of flooding, PUB engineers can take direct control of the Land Transport Authority's (LTA) traffic surveillance cameras via a console and joystick, to monitor and better manage the flood.

It is reminiscent of a scene in spy movie Jason Bourne, where the US Central Intelligence Agency takes control of the surveillance camera system in Athens to track down the renegade agent played by actor Matt Damon in real-time. "But we have LTA's permission," Mr Bernard Koh, the water agency's director of Water Supply (Plants), said with a laugh.

The Republic's water network is dispersed islandwide - from desalination plants in the west to reservoirs in the forested interior and the Changi Water Reclamation Plant in the east, linked by thousands of kilometres of drains and pipes.

All of it has to be monitored round-the-clock by at least one engineer and two assistant engineers in the control centre, to ensure the system runs like clockwork.

Mr Koh recalled getting occasional phone calls at 3am when there were plant disruptions due to equipment failure.

By Lin Yangchen, The Sunday Times, 12 Mar 2017

When a major fire broke out at a toxic waste management plant in Tuas last month, PUB engineers monitored the water supply to the hydrants to ensure firefighters had enough water to combat the blaze.

They also tracked drainage flows in the area, to check if any contaminated water from the fire was flowing to parts of the sea from which nearby desalination plants were drawing water.

They did so with a sophisticated real-time monitoring system in the national water agency's control centre, nestled somewhere in the Environment Building in Scotts Road.

The centre has 12 large screens and 16 smaller ones mounted on the wall, and many more on rows of consoles manned by engineers.

The screens display information on Singapore's water infrastructure in real-time - from detailed maps of water pipes and valves, to data on water pump pressure, flow rates and water quality. Set up in 2012 as part of PUB's Water Systems Unit, the control centre also draws information from other government agencies, like the National Environment Agency's weather radar.

When there is heavy rain and sensors in the canal warn of flooding, PUB engineers can take direct control of the Land Transport Authority's (LTA) traffic surveillance cameras via a console and joystick, to monitor and better manage the flood.

It is reminiscent of a scene in spy movie Jason Bourne, where the US Central Intelligence Agency takes control of the surveillance camera system in Athens to track down the renegade agent played by actor Matt Damon in real-time. "But we have LTA's permission," Mr Bernard Koh, the water agency's director of Water Supply (Plants), said with a laugh.

The Republic's water network is dispersed islandwide - from desalination plants in the west to reservoirs in the forested interior and the Changi Water Reclamation Plant in the east, linked by thousands of kilometres of drains and pipes.

All of it has to be monitored round-the-clock by at least one engineer and two assistant engineers in the control centre, to ensure the system runs like clockwork.

Mr Koh recalled getting occasional phone calls at 3am when there were plant disruptions due to equipment failure.

His staff needed him to assess the risk and decide how to respond.

The 47-year-old can securely log in to the system from anywhere using his iPad. "You check that the water levels at the affected service reservoirs are still okay, and how long you need to recover the plant (that supplies water to them). If you cannot do it by next morning's peak water use at 6am, you need other plants to come in and augment the supply," he said.

Water flows between plants and service reservoirs via multiple routes, making the system robust to the failure of any one part of it.

Mr Koh said his gynaecologist wife understands his occasionally erratic schedule, as she sometimes has to rush to hospital at odd hours too. "Both of us get called in the middle of the night," he quipped.

The centre's Web-based information technology also allows engineers to keep tabs on the water pipes buried in the ground.

There are 5,500km of potable water pipes and 3,500km of sewage pipes, including those extending to offshore islands such as Jurong Island and Sentosa, which are connected to the Singapore's main water grid. The potable water pipes are equipped with sensors that measure subtle changes in water pressure over time. This data is transmitted back to the control centre and compared to a baseline using data analytics, to detect anomalies that could indicate leaks.

Meanwhile, sewage pipes are equipped with sensors that detect chokages, allowing PUB to send men down to clear them before the sewage overflows onto the streets and becomes a health hazard.

There are 5,500km of potable water pipes and 3,500km of sewage pipes, including those extending to offshore islands such as Jurong Island and Sentosa, which are connected to the Singapore's main water grid. The potable water pipes are equipped with sensors that measure subtle changes in water pressure over time. This data is transmitted back to the control centre and compared to a baseline using data analytics, to detect anomalies that could indicate leaks.

Meanwhile, sewage pipes are equipped with sensors that detect chokages, allowing PUB to send men down to clear them before the sewage overflows onto the streets and becomes a health hazard.

For Mr Koh, water is a way of life. Although he is constantly on the alert for things like changes in the quality of reservoir water, he still finds it soothing to take a stroll with his daughter at MacRitchie Reservoir. "You can't really get away from water wherever you go, be it a drain, a (sewer) manhole, people using water. Water is part and parcel of our lives," he says.

Drastic action needed to cut water use here

Singapore uses more water than many other developed cities. Its target to cut water use from 151 litres per person to 140 litres by 2030 is not ambitious enough. A mix of pricing, incentives and behavioural change is needed before reservoirs dry up.

By Asit K. Biswas and Cecilia Tortajada, Published The Straits Times, 22 Mar 2017

On World Water Day today , it is appropriate to reflect on the future of Singapore's water.

The Singapore Government announced recently that the price of water will be increased in two stages. Mainstream and social media have been full of comments on its need, relevance and appropriateness.

Singapore last increased its water price in 2000, and thus, for 17 years, this price has remained constant. Almost a generation has grown up with no adjustment in water price. Electricity rates are significantly higher than those for water; they are adjusted regularly. Thus, whenever electricity rates are modified, there is seldom a ripple and it is not big news. However, when the water price is increased after 17 years and heftily so, it became a big news item.

The water price increase will be ameliorated greatly with increases in the value of the goods and services tax (GST) voucher. Families in one- and two-room HDB flats will receive $380 of U-Save rebates each year compared with $260, and families in three- and four-room HDB flats will receive $340 and $300 per year respectively, compared with $240 and $220. Consequently, on average, there will be no increase in the water bills for people in one- and two-room HDB households.

Consider some facts.

First, unquestionably, national water agency PUB has been an incredibly efficient institution. It has managed to increase its operational efficiency steadily so that it could balance its books until 2010, when it last made an operational profit of $48 million. From 2011, it has been making operating losses, which had to be made up by government grants. PUB losses have increased from $36 million in 2013 to $57.2 million in 2015.

Our studies indicate that between 2000 and 2014, because of inflation, water price decreased by 25.48 per cent in real terms. In contrast, electricity and gas prices have increased at a rate slightly higher than inflation.

In addition, the median income of employed resident households was $4,398 in 2000. This increased to $8,292 by 2014. Thus, assuming a household used 20 cubic m of water per month in 2000, the household's water bill represented 0.69 per cent of income. By 2014, it had declined to about 0.36 per cent.

Not surprisingly, a recent poll by The Straits Times showed that 75 per cent of Singaporeans had no idea what their water bill was.

FEAR DROUGHTS, NOT FLOODS

Singapore now needs to change the narrative from an argument of cost recovery for domestic and industrial water supply to one of managing a scarce, strategic and essential resource. For this, a profound societal mindset change is necessary as to how water should be managed in the future.

Singapore uses more water than many other developed cities. Its target to cut water use from 151 litres per person to 140 litres by 2030 is not ambitious enough. A mix of pricing, incentives and behavioural change is needed before reservoirs dry up.

By Asit K. Biswas and Cecilia Tortajada, Published The Straits Times, 22 Mar 2017

On World Water Day today , it is appropriate to reflect on the future of Singapore's water.

The Singapore Government announced recently that the price of water will be increased in two stages. Mainstream and social media have been full of comments on its need, relevance and appropriateness.

Singapore last increased its water price in 2000, and thus, for 17 years, this price has remained constant. Almost a generation has grown up with no adjustment in water price. Electricity rates are significantly higher than those for water; they are adjusted regularly. Thus, whenever electricity rates are modified, there is seldom a ripple and it is not big news. However, when the water price is increased after 17 years and heftily so, it became a big news item.

The water price increase will be ameliorated greatly with increases in the value of the goods and services tax (GST) voucher. Families in one- and two-room HDB flats will receive $380 of U-Save rebates each year compared with $260, and families in three- and four-room HDB flats will receive $340 and $300 per year respectively, compared with $240 and $220. Consequently, on average, there will be no increase in the water bills for people in one- and two-room HDB households.

Consider some facts.

First, unquestionably, national water agency PUB has been an incredibly efficient institution. It has managed to increase its operational efficiency steadily so that it could balance its books until 2010, when it last made an operational profit of $48 million. From 2011, it has been making operating losses, which had to be made up by government grants. PUB losses have increased from $36 million in 2013 to $57.2 million in 2015.

Our studies indicate that between 2000 and 2014, because of inflation, water price decreased by 25.48 per cent in real terms. In contrast, electricity and gas prices have increased at a rate slightly higher than inflation.

In addition, the median income of employed resident households was $4,398 in 2000. This increased to $8,292 by 2014. Thus, assuming a household used 20 cubic m of water per month in 2000, the household's water bill represented 0.69 per cent of income. By 2014, it had declined to about 0.36 per cent.

Not surprisingly, a recent poll by The Straits Times showed that 75 per cent of Singaporeans had no idea what their water bill was.

FEAR DROUGHTS, NOT FLOODS

Singapore now needs to change the narrative from an argument of cost recovery for domestic and industrial water supply to one of managing a scarce, strategic and essential resource. For this, a profound societal mindset change is necessary as to how water should be managed in the future.

Let us assess the current situation. At present, about 50 per cent of water used in Singapore comes from Johor. Due to the recent prolonged drought, storage at Johor's Linggiu Reservoir late last year was at a historic low.

On Jan 9, Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said in Parliament that there is a "significant risk" that the reservoir may not have any water if this year turns out to be dry. Fortunately, the storage is now more than 30 per cent, but nothing assures us that this may not change again in the coming months or years.

If Linggiu dries out, Singapore will lose not only half of its water supply, but there may also be a significant reduction in its Newater production. Newater is high-quality recycled wastewater. If the supply from Linggiu is cut by half, how would this affect wastewater generated and, thus, Newater production?

Add to this the potential uncertainty imposed by climate change, which is likely to contribute to prolonged droughts, as witnessed in many parts of the world.

Accordingly, the prudent strategy for Singapore will be to prepare for the time, not if but when, the supply from Linggiu will reduce to a trickle due to prolonged drought. In the last six years, we have regularly argued that it is not floods but droughts that Singapore needs to fear.

MAKE DRASTIC CUTS IN WATER USE

Current estimates suggest that by 2050, Singapore will need significantly higher amounts of water than what it currently consumes. Accordingly, efficient water management must receive priority national attention.

Even at current rates,domestic and industrial water usage is far too high for comfort. Both need to be reduced very significantly by judicious use of pricing, economic incentives, public education, awareness and, above all, behavioural changes.

Take domestic water use. In Singapore, domestic water consumption is over 50 per cent more than that in many other efficient cites. Per capita daily consumption in Singapore is about 150 litres. In contrast, developed cities like Malaga, Tallinn, Leipzig and Zaragoza have managed to reduce their per capita water consumption to less than 100 litres.

In the developing world, Sao Paulo reduced the average per capita daily consumption by an innovative pricing structure and good public awareness campaigns. If Paulista households reduced their water consumption compared with their use between February 2013 and January 2014, they received a generous rebate. If the reduction was between 10 per cent and 15 per cent, the rebate was 10 per cent. If it was over 20 per cent, the savings were 30 per cent. Concurrently, if households used 20 per cent more than the average, they had to pay a surcharge of 40 per cent. These actions reduced Sao Paulo's per capita water consumption from 143 litres in 2014 to 120 litres by 2015.

True, these cities are in different climates and lifestyles do differ. However, water conservation practices are what counts, and a combination of economic instruments, and attitudinal changes by developing a conservation ethics, ensured a more efficient use of water.

Singapore's current target is to reduce per capita water consumption to 147 litres by 2020 and to 140 litres by 2030. This, in our view, is too little, too late. The city-state should be much more ambitious.

MAKE DRASTIC CUTS IN WATER USE

Current estimates suggest that by 2050, Singapore will need significantly higher amounts of water than what it currently consumes. Accordingly, efficient water management must receive priority national attention.

Even at current rates,domestic and industrial water usage is far too high for comfort. Both need to be reduced very significantly by judicious use of pricing, economic incentives, public education, awareness and, above all, behavioural changes.

Take domestic water use. In Singapore, domestic water consumption is over 50 per cent more than that in many other efficient cites. Per capita daily consumption in Singapore is about 150 litres. In contrast, developed cities like Malaga, Tallinn, Leipzig and Zaragoza have managed to reduce their per capita water consumption to less than 100 litres.

In the developing world, Sao Paulo reduced the average per capita daily consumption by an innovative pricing structure and good public awareness campaigns. If Paulista households reduced their water consumption compared with their use between February 2013 and January 2014, they received a generous rebate. If the reduction was between 10 per cent and 15 per cent, the rebate was 10 per cent. If it was over 20 per cent, the savings were 30 per cent. Concurrently, if households used 20 per cent more than the average, they had to pay a surcharge of 40 per cent. These actions reduced Sao Paulo's per capita water consumption from 143 litres in 2014 to 120 litres by 2015.

True, these cities are in different climates and lifestyles do differ. However, water conservation practices are what counts, and a combination of economic instruments, and attitudinal changes by developing a conservation ethics, ensured a more efficient use of water.

Singapore's current target is to reduce per capita water consumption to 147 litres by 2020 and to 140 litres by 2030. This, in our view, is too little, too late. The city-state should be much more ambitious.

Between 1960 and 1970, Singapore carried out a unique study as to how much water an individual needed to lead a healthy life. It showed that at levels above 75 litres per day, there were no health benefits. An average Singaporean now uses twice this amount. Given that many European cities have progressively reduced their daily water consumption to less than 100 litres, Singapore needs to consider a much lower target of around 110 litres per day by 2035, which is achievable. By 2035, people in the most water-efficient cities will be using around 85 litres per day.

Finally, a mindset change is needed in terms of benchmarking good practices. Major technological breakthroughs often come from the developed world. However, many of the most significant policy breakthroughs are coming from the developing world. For example, Namibia's Windhoek has had direct potable use of treated wastewater for nearly 50 years. In the city of Jaipur, India, people know from their regular water bills how much public subsidies they are receiving.

Most Singaporeans in contrast do not know how much they pay for water, let alone that they do not pay for all of their water-related services themselves, as some are borne by the state. For example, the Government pays for all stormwater management services as public goods, which households in numerous cities pay directly through their water bills.

Given the strategic importance of water in Singapore, it is essential to engage the population in the formulation of future policies through a robust communication strategy with all the facts, figures and implications of possible decisions. This will ensure its water security for decades to come.

Professor Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, where Dr Cecilia Tortajada is Senior Research Fellow at its Institute of Water Policy.

Most Singaporeans in contrast do not know how much they pay for water, let alone that they do not pay for all of their water-related services themselves, as some are borne by the state. For example, the Government pays for all stormwater management services as public goods, which households in numerous cities pay directly through their water bills.

Given the strategic importance of water in Singapore, it is essential to engage the population in the formulation of future policies through a robust communication strategy with all the facts, figures and implications of possible decisions. This will ensure its water security for decades to come.

Professor Asit K. Biswas is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, where Dr Cecilia Tortajada is Senior Research Fellow at its Institute of Water Policy.

60km more water pipelines to be built over the next 2 years, including one in Punggol

Almost all will require deep tunnelling in parts; older ones to be renewed over next 2 years

By Aaron Chan, The Straits Times, 18 May 2017

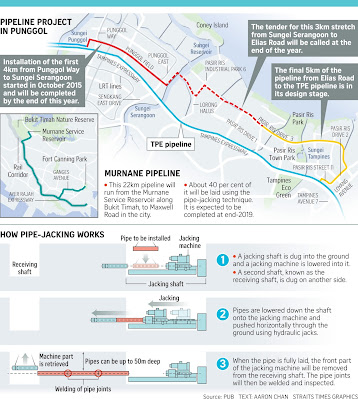

Some 60km of new potable water pipelines, including one in Punggol, will be built underground over the next two years to meet demands from new developments, national water agency PUB said yesterday.

Ninety per cent of these projects will require the use of pipe-jacking for some sections of the pipelines, said the agency. The method involves tunnelling beneath existing infrastructure, such as MRT tunnels, power cables, and drains.

Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli said yesterday: "We have to do this because our urban setting is more dense now. There is a lot of underground infrastructure that we have to bypass.The best way to do it is to go below (such structures), deep under them."

Mr Masagos was speaking during a visit to a pipe-jacking worksite in Tanglin Halt for the $365 million Murnane Pipeline - which is expected to be ready in 2019.

Pipe-jacking is about 21/2 times more expensive and slower than the open-cut method - where the ground is dug, pipes are laid and then covered back up. But it is also less disruptive to the daily lives of Singaporeans above areas where the tunnels are being built.

The 22km pipeline, which was first announced in 2014, with work starting in the second quarter last year, links the city to the Murnane Service Reservoir. It is named after Mr David Murnane, a pre-independence municipal water engineer. The pipeline is intended to meet future water demand, which is expected to double to about 115 million litres a day by 2060.

Mr Michael Toh, director of Water Supply Network at PUB, said: "Water pipes are laid to ensure that we are able to meet the growing needs of our customers."

Singapore's water network is planned and laid such that it is interconnected and able to provide alternative supplies if maintenance or repair is needed, he said.

Another pipeline in Punggol is also in the works to meet increased water demands there. It will serve future residential, commercial and industrial developments in the east, including Changi Airport and Tampines North New Town, said a PUB spokesman.

Almost all will require deep tunnelling in parts; older ones to be renewed over next 2 years

By Aaron Chan, The Straits Times, 18 May 2017

Some 60km of new potable water pipelines, including one in Punggol, will be built underground over the next two years to meet demands from new developments, national water agency PUB said yesterday.

Ninety per cent of these projects will require the use of pipe-jacking for some sections of the pipelines, said the agency. The method involves tunnelling beneath existing infrastructure, such as MRT tunnels, power cables, and drains.

Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli said yesterday: "We have to do this because our urban setting is more dense now. There is a lot of underground infrastructure that we have to bypass.The best way to do it is to go below (such structures), deep under them."

Mr Masagos was speaking during a visit to a pipe-jacking worksite in Tanglin Halt for the $365 million Murnane Pipeline - which is expected to be ready in 2019.

Pipe-jacking is about 21/2 times more expensive and slower than the open-cut method - where the ground is dug, pipes are laid and then covered back up. But it is also less disruptive to the daily lives of Singaporeans above areas where the tunnels are being built.

The 22km pipeline, which was first announced in 2014, with work starting in the second quarter last year, links the city to the Murnane Service Reservoir. It is named after Mr David Murnane, a pre-independence municipal water engineer. The pipeline is intended to meet future water demand, which is expected to double to about 115 million litres a day by 2060.

Mr Michael Toh, director of Water Supply Network at PUB, said: "Water pipes are laid to ensure that we are able to meet the growing needs of our customers."

Singapore's water network is planned and laid such that it is interconnected and able to provide alternative supplies if maintenance or repair is needed, he said.

Another pipeline in Punggol is also in the works to meet increased water demands there. It will serve future residential, commercial and industrial developments in the east, including Changi Airport and Tampines North New Town, said a PUB spokesman.

Over the past six years, the Punggol estate has doubled - from about 65,000 residents in 2011 to more than 130,000 last year - according to government data.

Aside from the Murnane and Punggol projects, new pipelines are slated for Tampines, Tuas and Tengah New Town.

PUB also announced that it will be renewing 75km of older pipelines over the next two years, as part of its routine maintenance and improvements. It has 5,500km of potable water pipelines under its charge.

On whether pipe-jacking has an impact on water prices, the Environment and Water Resources Ministry said in a statement: "Rising costs of asset maintenance and replacement, as well as of resources like chemicals, materials and manpower, have exerted upward pressures on the cost of water.

"A price increase is necessary now to ensure that PUB can continue to deliver a high quality and reliable water supply."

"A price increase is necessary now to ensure that PUB can continue to deliver a high quality and reliable water supply."

* The uphill battle for Singapore’s water security is set to continue

With climate change, maintaining and building on the resilience of our water systems will form the next chapter of Singapore’s water story.

By Shane Snyder, The Straits Times, 9 Nov 2023

As I leafed through the Forward Singapore (Forward SG) report and its messages on water resilience, I had a flashback to March 2008, when I received a letter that would forever change my life.

The letter was from Mr Khoo Teng Chye, chief executive of national water agency PUB, inviting me to attend the Water Leaders Summit during the first ever Singapore International Water Week (SIWW).

This “by-invitation only” letter signed in ink intrigued and enticed me to make the long journey to Singapore from the US in June of that year. I will never forget that first taxi ride from Changi to Suntec Convention Centre – indeed, I was instantly in awe of the beauty, cleanliness, and friendliness of Singapore.

I was impressed by what Singapore had accomplished, largely inspired by one of its founding fathers, Mr Lee Kuan Yew. From Newater to Marina Barrage to ocean desalination to imported water, Singapore had already established a brilliant portfolio of diverse sources of water.

Without question, water resilience was core to the success and sustainability of Singapore.

Threats to water resilience

At the most fundamental level, resilience can be interpreted as a secure supply of water. Once the supply is secured, engineered processes can convert nearly any type of water into pure, safe, and reliable supplies for homes and for industry.

However, complacency is the sleeping giant that can disrupt once-resilient water systems, especially with the impact brought by climate change. It is an existential threat to Singapore’s water supplies and to our water environment in general.

In 2019, drought across the Malaysian peninsula led to the reservoir level in Johor Bahru behind the Lebam Dam falling to less than 16 per cent. Fortunately, Singapore had three other national taps to rely upon as our imported water reached a critically low point. But prolonged drought in the region will also impact another national tap, our local catchments.

For instance, in February 2014, a severe drought led to extremely dry conditions in both Malaysia and Singapore, whereby Singapore was said to have experienced its driest February since 1869. During a severe drought, Singapore must rely predominantly on desalination to produce the water we all need and enjoy, on top of the water demands from our vibrant industries that drive the country’s economy.

In fact, it is estimated by PUB that by 2060, only 30 per cent of the water supply will be needed by homes while 70 per cent will be required by industrial and other non-domestic sector needs. Thus, Singapore will need to secure more water to expand and maintain this rapid non-domestic water demand.

Despite the diverse sources of water we have built over the years, meeting future demand is a huge task that comes with complex challenges.

Saving energy

Seawater is an infinite resource. But the processes to remove the salt from it are generally energy-intensive, around five times more energy than that for the production of Newater in which used water from our homes is collected, treated to very high standards, and then reused by high-tech industries and/or discharged into our freshwater reservoirs.

Singapore has also built large-scale desalination facilities that can treat freshwater, seawater, or even a blend of the two. This system is ideal as it can use far less pressure when urban catchments are full and turn to the ocean during periods of sustained drought.

In addition, my institute, Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute (Newri), as well as others are working hard to create novel processes that can lower the amount of energy required to desalinate ocean water, but also to increase resource recovery within the brine.

Seawater brine is generally discharged back into the sea, where it rapidly mixes and dilutes. However, this brine has numerous substances of value, such as magnesium, lithium, and others.

While seawater seems to be unlimited in supply, water quality challenges can and do occur that damage the system’s ability to function with the possibility of a shutdown.

Monitoring water quality

Today, Newri experts operate a fleet of drones fitted with hyperspectral cameras that can monitor for algal blooms, turbidity, and other anomalies that may negatively affect the desalination system. By monitoring the sea, we can better prepare for changing water quality or even shut down a facility if a serious issue is detected.

For instance, Singapore is one of the busiest shipping ports in the world and has some of the largest oil refineries in the world, with vast amounts of oil stored in bunkers along its coasts.

For these reasons, Singapore is uniquely prone to oil spills, and since 1960, Singapore and Malaysia together have suffered spills totalling at least 34 tonnes.

In August, an industrial fire near Raffles Marina spilt oil and other chemicals into the sea, killing many fish. These waters are precariously close to PUB’s water desalination system intakes near Tuas. Thus, even ocean desalination can be disrupted by human and natural events that change the water quality of the sea.

Likely, Singapore’s most daring and famous water success story is Newater.

Detecting anomalies

The Newater treatment system also uses reverse osmosis just as ocean desalination does; however, the lack of high concentrations of salt make the system far less energy-intensive.

Singapore also encourages companies with significant water use to develop their own water reuse systems to reduce the overall water consumption.

One challenge with water reuse is that in an extreme drought or if ocean desalination facilities are disrupted, there must be ample used water supply to recycle. Since Newater begins with what goes down our drains and through our sewer collection system, far greater treatment processes with increased monitoring are required to ensure public safety.

But considering that our sewer network is connected to thousands of homes and industries, it is difficult to know what chemicals are entering the system and whether they will be a challenge to remove using currently available technologies.

This provides another opportunity for innovation, such as sensor systems within the sewer collection network that can detect an anomaly, such as an illegal chemical disposal. Newater also can benefit from the advanced bioassay and analytical capabilities that have been procured and developed at Newri.

Today, there is funding from PUB to develop and deploy these tools in monitoring various water sources to attempt to identify new chemical contaminants as well as assess the toxicity to human cells.

Beyond homes and businesses

Though all water sources and systems face risks, such as climate change or chemical spills, Singapore continues to innovate to enhance the resilience of our water systems and to maintain utmost safety beyond what is required under regulations.

But our water journey in Singapore extends beyond the water we need and use for our homes and businesses.

The recent Forward SG report makes reference to the PUB’s programme Our Coastal Conversation, which had its inaugural meeting in October 2022. During the programme, various participants from diverse backgrounds were unanimous about the need for Singapore to protect its coastal area and community uses areas. They also agreed on the importance of maintaining biodiversity and green spaces along the coastline.

One participant said: “The key thing we want to retain is the beach front, intertidal area, and what this area represents to us. It is part of our psyche of what it means to be a Singaporean as an island nation.”

Reading such comments reinforces what I have learnt from the wonderful people I have met on my own, which is that, as an island nation, we must preserve our marine environment for the animals that call it home and for those who use it for recreation.

Indeed, the coast of Singapore provides habitat for many species of fish, phytoplankton, and even marine mammals. I was surprised to learn that among the dolphins and otters are also hawksbill turtles, considered critically endangered by Singapore and by the international community.

Since we need to discharge our concentrated brine from Newater and because we have a vibrant shipping port along with large refineries and chemical production facilities, keeping guard on our delicate marine systems will continue to be a challenge.

Fortunately, Singapore has what it takes in terms of talent and infrastructure to test and maintain this vibrant ecosystem and remain water-resilient using new technologies, superior education programmes, and through state-of-the-art pollution detection and monitoring systems.

We will have to remain resilient despite every growing threat to our waters, but together, I remain fully confident that Singapore will continue to see safe and reliable water, while at the same time protecting our coasts and recreational waters.

Shane Snyder is a professor of civil and environmental engineering and the executive director of the Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute at Nanyang Technological University.

Water prices to increase by 30% from 1 July 2017 in two phases

Strategic approach to water-planning crucial: DPM Teo

2017 Budget Statement debate in Parliament

Budget 2017: Moving Forward Together

Water price hike could have been better explained, but is necessary: PM Lee Hsien Loong