His presidency is a chance to shape race relations positively. Singapore still has some way to go.

By Mathew Mathews, Published The Straits Times, 6 Sep 2023

The election of Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam as Singapore’s ninth president stands as a profound testament to the nation’s commitment to racial inclusivity.

Mr Tharman’s resounding victory, with 70.4 per cent of the vote, realises an aspiration shared by many Singaporeans: to elect a competent and qualified president – whether from a minority race or otherwise – through an open contest in line with the nation’s commitment to meritocracy.

Race was almost a non-factor at the ballot box in some sense. Mr Tharman’s impeccable credentials, coupled with his popularity built over two decades in politics, overcame any lingering racial prejudices.

Racial representation in the presidency

Having good racial representation in the presidency is important for the development of multiracialism in Singapore. Recognising this, Parliament consistently appointed presidents from all the main racial groups in Singapore since Mr Yusof Ishak first assumed the role, even though there was no constitutional requirement to do so.

However, the public was sensitised to this objective only after constitutional amendments were passed in 2016 to reserve the elected presidency for candidates of a particular racial group if there had not been a president from that group for the five most recent presidential terms.

The population has largely come to accept these interventions as necessary to uphold the multiracial character of the presidency. In the 2021 CNA-IPS Survey on Race Relations, over 70 per cent of the 2,000 Singaporeans surveyed believed that the reserved presidency helped preserve racial harmony in Singapore.

Seeing a minority candidate win the race was never a given. The 2011 Presidential Election, featuring four candidates from the majority race, illustrated the growing challenges facing any qualified minority candidate in the race for the top job.

With qualifying conditions subsequently tightened, the very high bar for a nomination meant that only a small number of eminent minority representatives would be eligible to contest the president’s post. They, too, might be concerned that their chances of getting elected might be adversely impacted by the potential influence of racial preferences.

The high-water mark of race relations?

While Mr Tharman’s victory represents a significant milestone, it by no means signals that Singapore has fully transcended racial divisions and become a post-race society.

Race is unlikely to lose its significance entirely after Mr Tharman’s assumption of the presidency, just as it did not disappear as a political force in the United States after President Barack Obama’s historic election win in 2008.

Many observers have remarked on the irony that the mountain top of race relations in the US coincided with Mr Obama’s inauguration as the first African-American president, only to steadily deteriorate to the valleys through his tenure with heightening racial tensions ranging from the riots in Ferguson to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Singapore has been fortunate in maintaining generally positive race relations due to a combination of state interventions and the resolve of the population. Yet, racial preferences undeniably persist within the population, as highlighted by the same CNA-IPS survey. The survey showed high levels of in-group preferences for various roles, particularly among Chinese respondents.

When asked about the acceptability of different races to manage their business, nearly all were accepting of an ethnic Chinese in that role, although only about half were accepting of a Singaporean Malay (51.9 per cent) or Indian (52.8 per cent). Similar trends were evident when respondents were asked about renting a property to people of different racial groups or having someone from another race marry into the family.

It would be overly simplistic to attribute these racial preferences, and the general proclivity to see one another in terms of race, solely to state policies, such as the Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others system and the Ethnic Integration Policy in housing. Research suggests that some of these preferences may be ingrained from infancy and reinforced through early socialisation experiences.

Race in PE2023

Not only do racial preferences exist within the population, but efforts to mobilise racial sentiments in the context of the recent presidential election were also evident. Despite the guidelines given by the Elections Department to guard against campaign practices that may provoke racial or religious tensions, there were racially charged messages circulating on social media and instant messaging apps.

These included comments which alleged that the majority Chinese population needed a Chinese president to represent them after years of having a non-Chinese president, remarks that Mr Tharman was the champion of the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement, or Ceca – by now, a derogatory way of highlighting the presence of non-resident Indians working in Singapore – and attacks on the Japanese ancestry of Mr Tharman’s wife.

It is unclear where some of these messages originated from, or whether they were propagated by foreign actors seeking to sow discord or hatched locally. Yet, the mere fact that they were shared around, often without any criticism, underscores that these messages had traction with at least some Singaporeans.

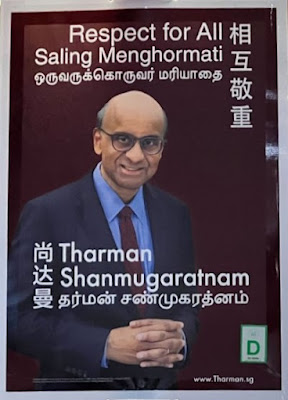

Recognising that race is never absent in elections, Mr Tharman conducted an energetic campaign to bridge potential gaps with demographic groups that might have hesitated to endorse an Indian candidate. His campaign slogan, “Respect for All”, and the use of the auspicious pineapple symbol were apt choices, resonating with Singapore’s culturally diverse population.

Towards a more racially harmonious society

While a post-racial Singapore may not be within immediate grasp despite President-elect Tharman’s successful election, his victory can further Singapore’s development into a more racially harmonious society.

The same CNA-IPS survey showed that since the reserved presidency in 2017 which saw Madam Halimah Yacob assume the role, the population has become more at ease with a Malay president, particularly among Chinese respondents. In 2016, 58.8 per cent of Chinese respondents, based on an earlier CNA-IPS survey, said they would accept a Malay president. This increased to 79.4 per cent in 2021.

Segments of the population, which may have been more wary before the reserved presidency was instituted, were won over by President Halimah’s performance in office, which may have dispelled any remaining prejudice and misconceptions over the suitability of Malays for the role of president.

Structures preserving racial harmony still needed

Still, it will be naive to think that Mr Tharman’s win is a strong enough justification that Singapore can do away with structures that maintain racial harmony, particularly the representation of minorities in politics through the group representation constituencies (GRC).

Opponents of the GRC system claim that racial minorities can and have stood for elections in single-member constituencies and been assessed by the electorate on their own merits, while voters would not be racially prejudiced as evidenced by Mr Tharman’s landslide win.

But this argument fails to recognise that Mr Tharman’s popularity today was possible only because he entered Parliament, and through the GRC system back in 2001.

There is insufficient evidence to suggest that racial preferences no longer matter in political contests to risk the situation where the lack of a mechanism to ensure racial representation in Parliament may result in one ethnic minority group being disproportionally under-represented in Parliament. This would have serious consequences for Singapore’s racial harmony.

Hopefully, the fact that Mr Tharman was endorsed by 70.4 per cent of Singaporeans will help those still harbouring doubts about the suitability of ethnic minorities for top positions to reconsider their stance. People should be evaluated based on the unique talents they bring rather than their ethnic origins.

Singapore’s journey towards racial harmony continues, and Mr Tharman’s victory is a pivotal chapter in that ongoing narrative.

Mr Tharman himself best articulated this in saying: “With each half decade, Singapore is changing and evolving. I hope that my being elected president is seen as another milestone in that process of evolution.”

Mathew Mathews is principal research fellow and head of the Social Lab at the Institute of Policy Studies at the National University of Singapore.

No comments:

Post a Comment