Over the past decade, government spending more than doubled from $33 billion to $71 billion - and is set to increase further. Ahead of Budget Day on Feb 19, Insight looks at where spending demands are greatest: healthcare, infrastructure and jobs. The first of a three-part series, this week's feature examines Singapore's social policies, and pressing issues in healthcare.

By Seow Bei Yi, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

Shaping policy in response to social needs is an ever-challenging - and changing - process. Just ask Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

Back in the mid-1990s when the Internet age was starting, many families were worried that their children would lose out because they could not afford computers.

The Government's solution: it would "socialise" computer use.

Public computers would be installed in schools and community centres, announced the Education Ministry's deputy secretary (policy) - Mr Tharman. There would be no subsidies for low-income families, he said then.

But as the Internet took off, this stance later changed. Government initiatives expanded to include subsidies for needy students to buy new computers and to subscribe to Internet broadband.

By Seow Bei Yi, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

Shaping policy in response to social needs is an ever-challenging - and changing - process. Just ask Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam.

Back in the mid-1990s when the Internet age was starting, many families were worried that their children would lose out because they could not afford computers.

The Government's solution: it would "socialise" computer use.

Public computers would be installed in schools and community centres, announced the Education Ministry's deputy secretary (policy) - Mr Tharman. There would be no subsidies for low-income families, he said then.

But as the Internet took off, this stance later changed. Government initiatives expanded to include subsidies for needy students to buy new computers and to subscribe to Internet broadband.

This flexibility to adapt to changing needs can be seen nowadays in the move to increase social spending for an inclusive society that gives the needy a leg-up. It stands in contrast to earlier years of nation-building, where the emphasis in social policy was self-reliance.

In an interview with Insight, Mr Tharman, who has been the Coordinating Minister for Economic and Social Policies since 2015, says:

"It's in the last decade that you see a decisive shift, a deliberate tilt, towards tempering the inequalities of life and ensuring the lower-income group keeps pace with the whole society as it moves up."

He outlines some of the key milestones: Workfare in 2007, which supports older low-wage Singaporeans who continue working and training; the Progressive Wage Model in 2012, which sets wage floors for workers' skill levels; SkillsFuture in 2015, which encourages lifelong learning; and MediShield Life, also in 2015, a health insurance plan helping to pay for costly hospital bills and treatments.

With such moves, social expenditure - which covers healthcare, education and social and family development, among others - ballooned to about $34 billion in 2016, from $12.7 billion a decade earlier. Last year, it comprised $37.8 billion - half of total government spending.

Experts agree there has been a shift to the left in Singapore's social policies - in terms of wealth redistribution - although they disagree as to the extent.

In the past, social support tended towards short-term aid for the unemployed, the ill, those with disabilities and the needy old, says National University of Singapore (NUS) economist Chia Ngee Choon, noting: "There was an aversion towards welfarism as it was feared that this may lead to a 'crutch mentality'."

But there was a growing acknowledgement that not everyone was benefiting from Singapore's economic growth. Some were falling way behind.

The 2005 Household Expenditure Survey showed that while average income for households rose 1.1 per cent annually from 1998 to 2003, those in the bottom 20 per cent saw their incomes fall 3.2 per cent a year in the same period.

By contrast, the Household Expenditure Survey in 2014 found that the income of those in the bottom 20 per cent rose at the highest rate of 6.6 per cent annually from 2008 to 2013, even as average monthly household income increased by 5.3 per cent annually.

AN AGEING, STRATIFYING NATION

The work is far from done, says Mr Tharman.

AN AGEING, STRATIFYING NATION

The work is far from done, says Mr Tharman.

The big challenges that Singapore faces are slowing social mobility and ageing, he says.

"They will be with us for a long while. They are not one-off challenges, not challenges for 10 or 15 years. They are challenges for decades to come."

His comments come amid sobering data.

One in four Singaporeans will be aged 65 and above in 12 years' time - by 2030. The figure today is about one in eight.

This dramatic shift in the population make-up is already propelling healthcare spending upwards, says Mr Tharman.

"Healthcare is the biggest challenge for the future of social spending. It's the fundamental reason why we need to raise more revenues, and why we have to spend effectively," he adds.

Other data also makes for grim reading. While Singapore's Gini coefficient - a measure of income inequality - fell to its lowest level in a decade in 2016, at 0.458, it remains one of the most unequal among developed societies. A lower coefficient suggests a more equal distribution of incomes.

Another set of statistics underscores the same trend.

The average monthly household income from work per household member for the top 10 per cent was $12,773 in 2016, over 23 times the $543 earned by those in the bottom 10 per cent of households.

The average monthly household income from work per household member for the top 10 per cent was $12,773 in 2016, over 23 times the $543 earned by those in the bottom 10 per cent of households.

In the year 2000, the corresponding figure for the top 10 per cent was $5,801, 18 times that of the $315 of those in the bottom 10 per cent.

As societies become more settled and class divisions firm up, one's starting advantage becomes a lasting advantage, says Mr Tharman. "It's true in every mature society, and the same can happen to us."

The Singaporean identity rests on the fact that everyone has a fair chance to move up the rungs of society, he notes, but it will take harder work to sustain this.

IS A TRAMPOLINE ENOUGH?

Asked by a BBC journalist at a gathering in Switzerland three years ago if Singapore believed in the notion of a safety net for those who fall between the cracks of a successful economy, Mr Tharman bounced back with a rejoinder that had the audience laughing, then applauding: "I believe in the notion of a trampoline."

During the interview, he elaborates. It is about helping people "with a difficult start" discover their own strengths - whether it is by helping them stay in work with Workfare, building their skills or helping them own their homes.

"This strengthens personal responsibility, and strengthens the sense of pride people get from contributing to their own lives and to society," he says. "That, I think, is the crucial social ethic that we've got to maintain. That is the Singapore approach, it can be done, and we've got to make sure that we sustain that into the future."

However, observers have also made the point that people at times make poor choices due to poor options.

Nanyang Technological University's (NTU) head of sociology Teo You Yenn notes in her new book This Is What Inequality Looks Like that a single mother, for instance, may find it tough to stay in her job due to a lack of childcare options.

Insight puts it to Mr Tharman that in such cases, people may be trying their hardest to bounce up on the metaphorical trampoline but are being hobbled by a broken ankle.

IS A TRAMPOLINE ENOUGH?

Asked by a BBC journalist at a gathering in Switzerland three years ago if Singapore believed in the notion of a safety net for those who fall between the cracks of a successful economy, Mr Tharman bounced back with a rejoinder that had the audience laughing, then applauding: "I believe in the notion of a trampoline."

During the interview, he elaborates. It is about helping people "with a difficult start" discover their own strengths - whether it is by helping them stay in work with Workfare, building their skills or helping them own their homes.

"This strengthens personal responsibility, and strengthens the sense of pride people get from contributing to their own lives and to society," he says. "That, I think, is the crucial social ethic that we've got to maintain. That is the Singapore approach, it can be done, and we've got to make sure that we sustain that into the future."

However, observers have also made the point that people at times make poor choices due to poor options.

Nanyang Technological University's (NTU) head of sociology Teo You Yenn notes in her new book This Is What Inequality Looks Like that a single mother, for instance, may find it tough to stay in her job due to a lack of childcare options.

Insight puts it to Mr Tharman that in such cases, people may be trying their hardest to bounce up on the metaphorical trampoline but are being hobbled by a broken ankle.

The Deputy Prime Minister responds that he does not mean that people have equal options.

Instead, a trampoline refers also to support from community networks: teachers, parents' support groups, friends and peers who help galvanise people with "a spirit of aspiration".

This, together with government help - Mr Tharman hints that KidStart, a pilot programme to give targeted attention to low-income pre-school children, will become "a major intervention" - will help people take "personal responsibility".

He warns: "If we do not sustain a culture of personal responsibility, you will get over time what we see now in several mature societies, which is a hardening of attitudes towards the poor."

For example, United States President Donald Trump last year sought to balance the federal budget with unprecedented cuts to programmes for poor and working-class families.

Yet, how much community support do the disadvantaged get, given that studies have shown a divide in social networks. A recent Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) survey found that someone who attended a non-elite school has ties to just 0.4 people who went to an elite school.

For Mr Tharman, what is key is avoiding "a culture of elitism". He exhorts: "Everyone must take a real interest in others in different stations of life from them. That's critical."

On whether that is happening enough in Singapore, he notes: "There is a risk that it will get eroded over time, and we have to work harder at it."

Can the Government also do more to enforce social mixing in its policies, for instance, in re-siting schools from the exclusive Bukit Timah enclave or in scrapping admission policies that entrench advantages across generations?

What is more important, responds Mr Tharman, is that schools around the island must offer quality: "Just assigning brand-name schools around the island doesn't itself do it."

CAN MORE BE DONE?

While observers welcome what has been achieved over the past decade, more can be done, they say.

On whether that is happening enough in Singapore, he notes: "There is a risk that it will get eroded over time, and we have to work harder at it."

Can the Government also do more to enforce social mixing in its policies, for instance, in re-siting schools from the exclusive Bukit Timah enclave or in scrapping admission policies that entrench advantages across generations?

What is more important, responds Mr Tharman, is that schools around the island must offer quality: "Just assigning brand-name schools around the island doesn't itself do it."

CAN MORE BE DONE?

While observers welcome what has been achieved over the past decade, more can be done, they say.

What is needed, argues Associate Professor Donald Low at NUS' Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, are universal schemes that better protect all workers - and not just low-income ones - from the pain of restructuring.

"Increasingly, we're going to find that people are moving a few times over the course of their careers, often into entirely new areas, because of the pace of technological and business model disruptions," says Dr Low.

Mr Tharman says that a critical policy on this front is SkillsFuture, which helps people reskill throughout their lives.

"It serves the needs of an innovative economy, but it is fundamentally a social strategy, too," he says, adding that this will go some way to help with social mobility.

"It is about becoming a meritocracy of skills, not one based on grades you earn early in life."

But re-training should not be the only measure for this affected group, say academics.

"It is about becoming a meritocracy of skills, not one based on grades you earn early in life."

But re-training should not be the only measure for this affected group, say academics.

Dr Low and IPS sociologist Mathew Mathews want a form of unemployment insurance to help workers tide over periods of job loss. Workers get payouts when they are rehired, giving them a greater incentive to take on new jobs.

As Singaporeans age, there are also growing calls for more of their healthcare needs to be taken care of - for instance, by putting in place a comprehensive insurance system for all ailments.

There is a particular need to help those who may have retired without enough savings - having spent their working years at a time where incomes and the cost of living were lower, says governance expert Neo Boon Siong of NTU.

"Today, the cost of living is high relative to the amount of savings they have," he notes. "How do you address the issue of equity?"

WHO PAYS?

As Singaporeans age, more will be done to care for them, says Mr Tharman. Money will then have to be raised. He puts it starkly thus: "There is no such thing as free healthcare in the world", as the bill is ultimately paid via taxes and insurance premiums.

Currently, the Government pays 70 per cent of the costs in the subsidised healthcare system. On whether the Government has ascertained that as the optimal level, he says that there is "no precise figure that we will claim to be optimal".

What is key is striking the right balance of individual spending, insurance and government subsidy collected through taxes, he says.

"If you rely too much on people paying for themselves, it will be inequitable. The poor will suffer.

"If you rely too much on insurance, where insurance is not just for big hospital bills like in MediShield Life but is much more comprehensive, then you get a problem of doctors over prescribing or the system gets overused."

With the Japanese universal health insurance system, for example, people visit physicians thrice as often as in other advanced countries and stay in hospitals two or three times longer, he says.

"We will continue tweaking it," Mr Tharman says of the balance.

Another issue Singapore stands firm on is the idea that subsidies and benefits must be targeted. "If everyone rich or poor gets the benefit of free healthcare, as your society ages, it becomes unaffordable," he says.

WHO PAYS?

As Singaporeans age, more will be done to care for them, says Mr Tharman. Money will then have to be raised. He puts it starkly thus: "There is no such thing as free healthcare in the world", as the bill is ultimately paid via taxes and insurance premiums.

Currently, the Government pays 70 per cent of the costs in the subsidised healthcare system. On whether the Government has ascertained that as the optimal level, he says that there is "no precise figure that we will claim to be optimal".

What is key is striking the right balance of individual spending, insurance and government subsidy collected through taxes, he says.

"If you rely too much on people paying for themselves, it will be inequitable. The poor will suffer.

"If you rely too much on insurance, where insurance is not just for big hospital bills like in MediShield Life but is much more comprehensive, then you get a problem of doctors over prescribing or the system gets overused."

With the Japanese universal health insurance system, for example, people visit physicians thrice as often as in other advanced countries and stay in hospitals two or three times longer, he says.

"We will continue tweaking it," Mr Tharman says of the balance.

Another issue Singapore stands firm on is the idea that subsidies and benefits must be targeted. "If everyone rich or poor gets the benefit of free healthcare, as your society ages, it becomes unaffordable," he says.

Finland, for instance, has a universal system where rich and poor get benefits. And it is getting harder to afford as the population ages, he says. This has led to cutbacks in other areas such as higher education, with young people leaving the country.

NOTHING IS SACROSANCT

Ask Mr Tharman what scope there is for the Government to review its thinking on "sacred cows" - and he maintains that there are none.

NOTHING IS SACROSANCT

Ask Mr Tharman what scope there is for the Government to review its thinking on "sacred cows" - and he maintains that there are none.

There have long been robust calls for policies such as a minimum wage - which have just been as vigorously dismissed. Economist Lim Chong Yah, founding chairman of the National Wages Council, has advocated for a legislated minimum wage, arguing that Singapore had swung too much towards growth at the expense of equity in the last decade or so.

Asked whether the Government's stance could shift, Mr Tharman says: "If we come to a point where our current approach no longer leads to broad-based income growth, and that you find that year after year, the bottom 10 per cent, bottom 20 per cent, is slipping further away from the rest of the population, then we may need new approaches."

Asked whether the Government's stance could shift, Mr Tharman says: "If we come to a point where our current approach no longer leads to broad-based income growth, and that you find that year after year, the bottom 10 per cent, bottom 20 per cent, is slipping further away from the rest of the population, then we may need new approaches."

But so far, these lower-income groups have had "as fast or faster income growth" as the rest of the workforce, he points out.

"The most important way we can provide for social well-being across the full span of the population is to have a vibrant economy," says Mr Tharman.

In a Cabinet which devotes long hours to debating issues, "nothing is sacrosanct", states the minister.

He cites the Progressive Wage Model - which sets the minimum wages of low-wage workers in certain jobs - which he says would not have been introduced 20 years ago. "But we did it, because even with jobs being available for all, even with a relatively healthy economy, we found that some workers were not being fairly treated - particularly in industries where there was a lot of outsourcing."

Asked if the idea that nothing is sacrosanct is a thinking that permeates throughout the Cabinet, he replies: "I would say so.

"We take a practical approach towards social and economic policy, not embedded in ideology."

With Singapore caught up in the issue of leadership succession, Insight asks: Is it an approach that the next generation of leaders have as well?

Mr Tharman bounces back with: "Very much so. They have open minds."

Mr Tharman bounces back with: "Very much so. They have open minds."

Finding a cure for rising costs in healthcare

The health budget in two years is expected to be almost on a par with that of defence now, traditionally the biggest government spending item. Even as spending has to go up, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong maps out to Insight Singapore's strategy for keeping cost increases under control.

By Yuen Sin, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

In 2011, Dr Wong Sweet Fun and her colleagues from the newly set up Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) in Yishun began seeing a trend of high re-admission rates, especially among elderly patients and those with chronic conditions.

It turned out that a lack of coordinated care and support for patients - such as follow-up visits by doctors and nurses in their homes - prevented them from taking charge of their health, says the 57-year-old senior consultant in geriatric medicine at KTPH.

A programme to address this was launched the same year. Among other things, it sends nurses to patients' homes to provide follow-up care. As a result, the average six-month re-admission rate for the first 400 patients on the scheme was slashed by over 60 per cent.

The increased emphasis on primary care and prevention is an outcome that might give heart to policymakers trying to work out how to pay for ballooning healthcare costs, which are in the spotlight ahead of next month's Budget, amid talk of raising taxes.

Come 2030, those aged 65 and above will almost double in number to comprise a quarter of Singaporeans.

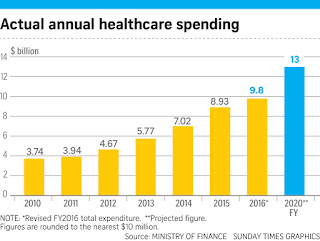

And in two years, healthcare spending is expected to be almost on a par with that of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Defence currently - traditionally one of the highest among all ministries.

This, even as countries in the region spend more than ever on defence amid terrorism and cyber security threats.

But while healthcare costs go up, given Singapore's ageing population, a quiet revolution in healthcare spending policy is taking place to stop spending from ballooning.

REBALANCING ACT

One big effect of this demographic clustering will be a shift in disease patterns towards chronic diseases.

Whether this pattern occurs at a slower or faster pace depends on whether Singaporeans can stay healthy, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) is taking steps to encourage this.

Just as how the Education Ministry espouses the belief that "every school is a good school", Health Minister Gan Kim Yong says that "all doctors are good doctors".

Just two in five Singapore residents now see a regular family doctor, as some still think that hospital specialist care is superior, and some hop between doctors.

However, Mr Gan wants that figure to go up to five out of five eventually, including those who see a regular team of healthcare professionals.

When that happens, primary care can become the bedrock of Singapore's healthcare system, with chronic conditions managed by a network of general practitioners (GPs), polyclinics and community organisations, while hospital services are tapped only in cases of need - a shift away from the current more hospital-centric model.

When GPs and polyclinic doctors see patients at the start of chronic ailments, they will be able to delay or prevent the progression of these diseases into more complex conditions that will cost a lot more to treat in hospital. For example, uncontrolled diabetes may lead to kidney failure and stroke.

Seeing regular family doctors ensures continuity. A closer, trusting relationship between the patient and a regular team of healthcare professionals will lead to more personalised management of their various conditions. This results in optimised treatments and, ultimately, lower healthcare costs.

To tip the scales in this rebalancing act, MOH is investing more in primary care.

For example, subsidies under the Community Health Assist Scheme - catering to lower-and middle-income patients who see private GPs - have been enhanced over the years.

Private-public healthcare collaboration is also being encouraged.

The health budget in two years is expected to be almost on a par with that of defence now, traditionally the biggest government spending item. Even as spending has to go up, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong maps out to Insight Singapore's strategy for keeping cost increases under control.

By Yuen Sin, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

In 2011, Dr Wong Sweet Fun and her colleagues from the newly set up Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) in Yishun began seeing a trend of high re-admission rates, especially among elderly patients and those with chronic conditions.

It turned out that a lack of coordinated care and support for patients - such as follow-up visits by doctors and nurses in their homes - prevented them from taking charge of their health, says the 57-year-old senior consultant in geriatric medicine at KTPH.

A programme to address this was launched the same year. Among other things, it sends nurses to patients' homes to provide follow-up care. As a result, the average six-month re-admission rate for the first 400 patients on the scheme was slashed by over 60 per cent.

The increased emphasis on primary care and prevention is an outcome that might give heart to policymakers trying to work out how to pay for ballooning healthcare costs, which are in the spotlight ahead of next month's Budget, amid talk of raising taxes.

Come 2030, those aged 65 and above will almost double in number to comprise a quarter of Singaporeans.

And in two years, healthcare spending is expected to be almost on a par with that of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Defence currently - traditionally one of the highest among all ministries.

This, even as countries in the region spend more than ever on defence amid terrorism and cyber security threats.

But while healthcare costs go up, given Singapore's ageing population, a quiet revolution in healthcare spending policy is taking place to stop spending from ballooning.

REBALANCING ACT

One big effect of this demographic clustering will be a shift in disease patterns towards chronic diseases.

Whether this pattern occurs at a slower or faster pace depends on whether Singaporeans can stay healthy, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) is taking steps to encourage this.

Just as how the Education Ministry espouses the belief that "every school is a good school", Health Minister Gan Kim Yong says that "all doctors are good doctors".

Just two in five Singapore residents now see a regular family doctor, as some still think that hospital specialist care is superior, and some hop between doctors.

However, Mr Gan wants that figure to go up to five out of five eventually, including those who see a regular team of healthcare professionals.

When that happens, primary care can become the bedrock of Singapore's healthcare system, with chronic conditions managed by a network of general practitioners (GPs), polyclinics and community organisations, while hospital services are tapped only in cases of need - a shift away from the current more hospital-centric model.

When GPs and polyclinic doctors see patients at the start of chronic ailments, they will be able to delay or prevent the progression of these diseases into more complex conditions that will cost a lot more to treat in hospital. For example, uncontrolled diabetes may lead to kidney failure and stroke.

Seeing regular family doctors ensures continuity. A closer, trusting relationship between the patient and a regular team of healthcare professionals will lead to more personalised management of their various conditions. This results in optimised treatments and, ultimately, lower healthcare costs.

To tip the scales in this rebalancing act, MOH is investing more in primary care.

For example, subsidies under the Community Health Assist Scheme - catering to lower-and middle-income patients who see private GPs - have been enhanced over the years.

Private-public healthcare collaboration is also being encouraged.

A scheme where hospitals get funding support to refer stable patients from specialist outpatient clinics to GP partners was initiated by MOH in 2014.

Last year, it rolled out a scaled-up primary care network scheme to GPs, after being piloted in 2012.

These groupings allow individual doctors to pool resources and offer services such as health counselling provided by their nurses, and eye screening for diabetics, which they would not be able to provide on their own.

There are now 10 such networks, with 340 GPs on board.

Of course, it is all the better if Singaporeans can remain active and keep visits to the doctor at bay.

These groupings allow individual doctors to pool resources and offer services such as health counselling provided by their nurses, and eye screening for diabetics, which they would not be able to provide on their own.

There are now 10 such networks, with 340 GPs on board.

Of course, it is all the better if Singaporeans can remain active and keep visits to the doctor at bay.

Sometimes, all it takes is one simple step, says Mr Gan, who is also chairman of the Ministerial Committee on Ageing.

An opportunity to start doing so was just a few metres away from his office on the third floor of the College of Medicine building in Outram, where a broken-down lift forced staff and the 58-year-old minister to take the stairs earlier this month.

He says: "(This) is a good thing. So I joked with the staff, 'Maybe we should never repair it, just leave it as it is and we walk every day.'"

THE DOLLARS BEHIND THE DECISIONS

In Budget 2017, $10 billion was allocated for healthcare expenditure, and the amount is expected to go up to at least $13 billion by 2020.

This will rival the $14 billion and $12.9 billion allocated to defence and education expenditure in Budget 2017 respectively.

Between 2010 and 2015, the Government's share of overall national healthcare expenditure, including private healthcare costs, grew from about 35 per cent to more than 40 per cent. As a partial result, the share of the individual's contribution fell from about 40 per cent to about 30 per cent.

In terms of finances, maintaining a balance between three components - individuals paying, risk-pooling through insurance schemes such as MediShield Life and, finally, government subsidies - is critical, Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam tells Insight, adding that the Government currently pays for 70 per cent of the subsidised healthcare system.

On whether the Government's share of the bill will rise above the current 70 per cent, Mr Gan says: "It may be 70 per cent, it may be 60 per cent, it may be 80 per cent, we don't know."

He noted that this will include capital expenditure, such as the costs of building new hospitals - three of which will be ready by 2020.

The Government should never wind up paying for 100 per cent of subsidised healthcare, because this creates a "pretence" that healthcare is free in Singapore, warns Mr Tharman. "If you go to 100 per cent, it means people will just pay vastly more taxes."

TOUCH AND HOLD, NOT TOUCH AND GO

When 45-year-old MOH deputy secretary for development Teoh Zsin Woon was in primary school, the way in which healthcare was delivered to students via the School Health Service operated "like clockwork".

"You get nagged to brush your teeth by the drain (as part of a nationwide campaign), the school asks you to go to the dental clinic, the nurse will come to check your body weight, height and eyes, and they will also get your vaccinations done," says Ms Teoh, who has spent a substantial part of the past year shadowing community volunteers on home visits to seniors in older neighbourhoods.

But as generations before her graduated from schools and started to age within the four walls of their homes, the lack of a standardised model that can bring basic healthcare services to one's doorstep has produced a gap that Ms Teoh dubs "the social last mile".

The lines between healthcare and social support have increasingly become blurred, but health and social care providers may not be adapting well to this change on the ground, she notes.

For example, an elderly man living on his own may be able to see the best doctor in a specialist clinic, but all that comes to nought if he forgets to take his medication, or if there is nobody to take him to the doctor for regular appointments.

Another elderly woman may have bought a blood pressure monitor, but her condition will not improve if she is not taught how to monitor her blood pressure daily.

Such a "touch and go" approach where specific responsibilities are neatly delegated to different institutions has to go when it comes to helping elderly patients, she declares.

THE DOLLARS BEHIND THE DECISIONS

In Budget 2017, $10 billion was allocated for healthcare expenditure, and the amount is expected to go up to at least $13 billion by 2020.

This will rival the $14 billion and $12.9 billion allocated to defence and education expenditure in Budget 2017 respectively.

Between 2010 and 2015, the Government's share of overall national healthcare expenditure, including private healthcare costs, grew from about 35 per cent to more than 40 per cent. As a partial result, the share of the individual's contribution fell from about 40 per cent to about 30 per cent.

In terms of finances, maintaining a balance between three components - individuals paying, risk-pooling through insurance schemes such as MediShield Life and, finally, government subsidies - is critical, Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam tells Insight, adding that the Government currently pays for 70 per cent of the subsidised healthcare system.

On whether the Government's share of the bill will rise above the current 70 per cent, Mr Gan says: "It may be 70 per cent, it may be 60 per cent, it may be 80 per cent, we don't know."

He noted that this will include capital expenditure, such as the costs of building new hospitals - three of which will be ready by 2020.

The Government should never wind up paying for 100 per cent of subsidised healthcare, because this creates a "pretence" that healthcare is free in Singapore, warns Mr Tharman. "If you go to 100 per cent, it means people will just pay vastly more taxes."

TOUCH AND HOLD, NOT TOUCH AND GO

When 45-year-old MOH deputy secretary for development Teoh Zsin Woon was in primary school, the way in which healthcare was delivered to students via the School Health Service operated "like clockwork".

"You get nagged to brush your teeth by the drain (as part of a nationwide campaign), the school asks you to go to the dental clinic, the nurse will come to check your body weight, height and eyes, and they will also get your vaccinations done," says Ms Teoh, who has spent a substantial part of the past year shadowing community volunteers on home visits to seniors in older neighbourhoods.

But as generations before her graduated from schools and started to age within the four walls of their homes, the lack of a standardised model that can bring basic healthcare services to one's doorstep has produced a gap that Ms Teoh dubs "the social last mile".

The lines between healthcare and social support have increasingly become blurred, but health and social care providers may not be adapting well to this change on the ground, she notes.

For example, an elderly man living on his own may be able to see the best doctor in a specialist clinic, but all that comes to nought if he forgets to take his medication, or if there is nobody to take him to the doctor for regular appointments.

Another elderly woman may have bought a blood pressure monitor, but her condition will not improve if she is not taught how to monitor her blood pressure daily.

Such a "touch and go" approach where specific responsibilities are neatly delegated to different institutions has to go when it comes to helping elderly patients, she declares.

In its place, institutions must "touch and hold" - wrap a patient into the embrace of various care services that can detect and coordinate services around his needs, instead of subjecting him to the impossible challenge of navigating a complex labyrinth of services on his own.

Ms Teoh is now hawking a set of "ABCs" in her push to address this gap: Active ageing, Befriending, and Care and support.

One of the initiatives under this vision is MOH's Community Network for Seniors scheme, which was piloted in April 2016 and aims to enhance integration and the pooling of resources for services related to the elderly.

It has linked up more than 600 seniors who live alone with befrienders or volunteers, and referred about 800 seniors with complex needs to MOH. But problems remain, such as the duplication of efforts in some areas and the under-detection of other needs.

"We are definitely not there yet," she admits. And time is not on her side, as MOH needs to ramp up its efforts to meet Singapore's increased demand in this area by 2030.

But even as hospitals are being built and options for assisted living services or developments are being studied, the delivery of care, she stresses, does not have to hinge on the existence of bricks-and-mortar facilities or even the headcounts of doctors and nurses.

By working with partners such as Pioneer Generation Ambassadors, MOH can detect what are the needs on the ground, and direct services and resources to available community spaces. For example, exercise programmes for the elderly conducted by the Health Promotion Board need not be restricted solely to senior activity centres.

They can also be done at residents' committee centres or community clubs in neighbourhoods with elderly people who have not been keeping active.

Instead of building hospitals nearby, new community nursing posts can also be set up in these spaces to help elderly patients manage chronic conditions.

Age, she says, is relative, pointing out how 70-year-olds are able to care for 100-year-olds in resilient communities such as in Japan, and how older volunteers are commonly seen in community befriending programmes for seniors here.

Her minister agrees.

In fact, Mr Gan advocates raising the re-employment age beyond the current 67 years old gradually, and lifting it altogether eventually.

Seniors who are willing and able to work should be allowed to do so for as long as they want, even as he also wants to encourage senior volunteerism for those who do not want or need to work.

These are "important issues" that he discusses from time to time with Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say.

Asked why the re-employment age cannot be removed right away, he says that this would be a burden on employers, given that current laws prescribe that employers have to provide an Employment Assistance Payment if they are unable to offer re-employment to eligible employees who turn 62.

It has linked up more than 600 seniors who live alone with befrienders or volunteers, and referred about 800 seniors with complex needs to MOH. But problems remain, such as the duplication of efforts in some areas and the under-detection of other needs.

"We are definitely not there yet," she admits. And time is not on her side, as MOH needs to ramp up its efforts to meet Singapore's increased demand in this area by 2030.

But even as hospitals are being built and options for assisted living services or developments are being studied, the delivery of care, she stresses, does not have to hinge on the existence of bricks-and-mortar facilities or even the headcounts of doctors and nurses.

By working with partners such as Pioneer Generation Ambassadors, MOH can detect what are the needs on the ground, and direct services and resources to available community spaces. For example, exercise programmes for the elderly conducted by the Health Promotion Board need not be restricted solely to senior activity centres.

They can also be done at residents' committee centres or community clubs in neighbourhoods with elderly people who have not been keeping active.

Instead of building hospitals nearby, new community nursing posts can also be set up in these spaces to help elderly patients manage chronic conditions.

Age, she says, is relative, pointing out how 70-year-olds are able to care for 100-year-olds in resilient communities such as in Japan, and how older volunteers are commonly seen in community befriending programmes for seniors here.

Her minister agrees.

In fact, Mr Gan advocates raising the re-employment age beyond the current 67 years old gradually, and lifting it altogether eventually.

Seniors who are willing and able to work should be allowed to do so for as long as they want, even as he also wants to encourage senior volunteerism for those who do not want or need to work.

These are "important issues" that he discusses from time to time with Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say.

Asked why the re-employment age cannot be removed right away, he says that this would be a burden on employers, given that current laws prescribe that employers have to provide an Employment Assistance Payment if they are unable to offer re-employment to eligible employees who turn 62.

"It is better for us to work with the employers now in a collective effort, and that has always been the way we work with employment issues - in a tripartite manner," he says.

Other improvements to the integration of community health and social services are under way.

This month, MOH and the Pioneer Generation Office began organising "kampung meetings", where staff from the regional health systems, community nurses, social service organisations, the People's Association and senior activity or care centres are brought together to share plans and coordinate the services that can be offered or hosted by various organisations.

Care Line - a 24/7 telephone helpline for seniors launched in the eastern region in November 2016 - was expanded to cover Tanjong Pagar and Radin Mas this month.

Ms Teoh says she is unsure if she can ever declare success in such efforts, as new needs will emerge along the way.

She adds: "But we are trying to take a perspective that is no longer institution-centric, and provide seniors with a service that is equivalent to what was offered by the School Health Service in the past."

Ms Teoh says she is unsure if she can ever declare success in such efforts, as new needs will emerge along the way.

She adds: "But we are trying to take a perspective that is no longer institution-centric, and provide seniors with a service that is equivalent to what was offered by the School Health Service in the past."

More home-based care options likely for seniors

Government studying assisted living facilities or services, reveals health minister

By Yuen Sin, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

Singaporeans may soon have the option of remaining at home - with the necessary personal and nursing care around the clock - as they grow old, sickly and less able.

A new offering is now under study: assisted living facilities or services, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong disclosed in an interview with The Sunday Times.

They allow seniors with physical or mental health needs and varying degrees of mobility to retain their independence by living at home, instead of in a more institutionalised setting such as a nursing home.

The options being considered may include shared residences, where three to four seniors live together and share common areas. They could also live with their families, with personal or home care services offered. These could be layered on as and when required. For instance, a senior may start out just needing help with meals but can get more aid including nursing care when he becomes more frail.

Mr Gan said the Ministry of Health (MOH) is looking into how to provide more such eldercare help - commonly seen in countries such as Finland and Japan - as the pace of ageing in Singapore quickens. He declined to disclose further details on the likely options, which he said will be announced in the near future. His ministry would likely carry out pilot projects, including determining if assisted living models can be developed in the current configuration of HDB estates.

In recent years, small pockets of assisted living options have been explored in Singapore. For instance, the integrated HDB development Kampung Admiralty, which opened last August, will offer services such as those of a handyman or home medical and nursing care. But they are limited: for example, there is no caregiver on standby for those with dementia.

Another is St Bernadette Lifestyle Village, a private facility in Bukit Timah Road that provides a 24-hour medical concierge and meals, if required. Its eight residents get help to live independently, including going on supervised trips to shopping malls. Fees are at $3,650 a month.

By 2030, almost one in three of those in Singapore is forecast to need some form of eldercare service. One in four Singaporeans will be aged 65 and above.

But a 2016 report, commissioned by the Lien Foundation and Khoo Chwee Neo Foundation on nursing homes, found that seniors have few housing options apart from living in a nursing home if they grow frail and do not have anyone to care for them at home.

Ms Teoh Zsin Woon, MOH's deputy secretary for development, said assisted living facilities abroad often take the form of gated communities. But Singapore's dense HDB clusters are an advantage that should be tapped, she said.

MOH will study how seniors can get help to age in place within their HDB homes, and possibly offer options beyond what Kampung Admiralty now provides, said Ms Teoh. It will also look at new HDB estates and other projects to work on how they can be better designed to support care for seniors, she added.

Lien Foundation chief executive Lee Poh Wah believes assisted living is an attractive option. Many Singaporeans are in nursing homes not because they need skilled nursing or medical care, but because they need personal care such as help with dressing or going to the toilet, he said. He suggested building group homes for seniors on one or two floors of an HDB or condominium block, and offering them to those who want to downsize.

Ms Peh Kim Choo, chief executive of Tsao Foundation, said the "litmus test" of assisted living in Singapore is whether a person can continue to stay put even as his physical and mental health condition changes as he grows older.

"At the same time, it needs to answer to people's needs for connection, growth and development to eradicate depression and social isolation."

Related

The Straits Times Interview with DPM Tharman Shanmugaratnam

Govt spending on healthcare expected to rise sharply; Singapore faces demographic time bomb in 2018

How to fund spending on elderly - higher taxes or tap national reserves? Singaporeans divided

Institute of Policy Studies Singapore Perspectives 2018 conference

Government studying assisted living facilities or services, reveals health minister

By Yuen Sin, The Sunday Times, 28 Jan 2018

Singaporeans may soon have the option of remaining at home - with the necessary personal and nursing care around the clock - as they grow old, sickly and less able.

A new offering is now under study: assisted living facilities or services, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong disclosed in an interview with The Sunday Times.

They allow seniors with physical or mental health needs and varying degrees of mobility to retain their independence by living at home, instead of in a more institutionalised setting such as a nursing home.

The options being considered may include shared residences, where three to four seniors live together and share common areas. They could also live with their families, with personal or home care services offered. These could be layered on as and when required. For instance, a senior may start out just needing help with meals but can get more aid including nursing care when he becomes more frail.

Mr Gan said the Ministry of Health (MOH) is looking into how to provide more such eldercare help - commonly seen in countries such as Finland and Japan - as the pace of ageing in Singapore quickens. He declined to disclose further details on the likely options, which he said will be announced in the near future. His ministry would likely carry out pilot projects, including determining if assisted living models can be developed in the current configuration of HDB estates.

In recent years, small pockets of assisted living options have been explored in Singapore. For instance, the integrated HDB development Kampung Admiralty, which opened last August, will offer services such as those of a handyman or home medical and nursing care. But they are limited: for example, there is no caregiver on standby for those with dementia.

Another is St Bernadette Lifestyle Village, a private facility in Bukit Timah Road that provides a 24-hour medical concierge and meals, if required. Its eight residents get help to live independently, including going on supervised trips to shopping malls. Fees are at $3,650 a month.

By 2030, almost one in three of those in Singapore is forecast to need some form of eldercare service. One in four Singaporeans will be aged 65 and above.

But a 2016 report, commissioned by the Lien Foundation and Khoo Chwee Neo Foundation on nursing homes, found that seniors have few housing options apart from living in a nursing home if they grow frail and do not have anyone to care for them at home.

Ms Teoh Zsin Woon, MOH's deputy secretary for development, said assisted living facilities abroad often take the form of gated communities. But Singapore's dense HDB clusters are an advantage that should be tapped, she said.

MOH will study how seniors can get help to age in place within their HDB homes, and possibly offer options beyond what Kampung Admiralty now provides, said Ms Teoh. It will also look at new HDB estates and other projects to work on how they can be better designed to support care for seniors, she added.

Lien Foundation chief executive Lee Poh Wah believes assisted living is an attractive option. Many Singaporeans are in nursing homes not because they need skilled nursing or medical care, but because they need personal care such as help with dressing or going to the toilet, he said. He suggested building group homes for seniors on one or two floors of an HDB or condominium block, and offering them to those who want to downsize.

Ms Peh Kim Choo, chief executive of Tsao Foundation, said the "litmus test" of assisted living in Singapore is whether a person can continue to stay put even as his physical and mental health condition changes as he grows older.

"At the same time, it needs to answer to people's needs for connection, growth and development to eradicate depression and social isolation."

Related

The Straits Times Interview with DPM Tharman Shanmugaratnam

Govt spending on healthcare expected to rise sharply; Singapore faces demographic time bomb in 2018

How to fund spending on elderly - higher taxes or tap national reserves? Singaporeans divided

Institute of Policy Studies Singapore Perspectives 2018 conference

No comments:

Post a Comment