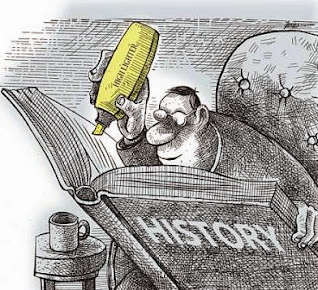

That Singaporeans remember some events of the past better than others is linked to a new generation wanting to rewrite history to better understand the times they live in

By Kwa Chong Guan, Published The Straits Times, 30 Jan 2015

By Kwa Chong Guan, Published The Straits Times, 30 Jan 2015

THE findings of a recent Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) survey about the best remembered and least remembered events of Singapore's past have started another cycle of soul-searching on whether we are forgetting our history and, if so, what we should do about it.

The survey revealed that a low 16.6 per cent of the 1,500 citizens polled were aware of the 1963 detention of 113 persons for alleged communist activities, an incident dubbed Operation Coldstore. This was despite a new cycle of debates among a younger generation of historians challenging the official account that these 113 and others were engaged in communist activities.

There appears to be some concern that, in not remembering Operation Coldstore, Singaporeans are forgetting a key historical event of our past which we should be more aware of than the opening of the two casinos in 2010 - which topped the list of events that Singaporeans could recall. Explanations that the opening of the two casinos is a recent event which people can recall, in contrast to Operation Coldstore, which occurred 52 years ago, are not sufficient.

Some 89.8 per cent of those polled were aware of an event which occurred almost 200 years ago: Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles' landing on this island. It also cannot be that we are more aware of events which impact our daily lives - like breakdowns of the MRT trains or the Sars outbreak - and unaware of political events such as opposition politician J.B. Jeyaretnam's 1981 victory in the Anson by-elections because their connections to us today are forgotten.

Recency does not sufficiently explain the lack of awareness of key political events. Nor is the issue merely that of alternative versions of our history and how to decide objectively which version to accept. I believe what we are seeing is a highly charged contest about rewriting history to understand our present and prospects for the future.

Post-1965 to post-Cold War

OUR pre-World War II generation who grew up under British colonial rule learnt about Singapore's history as part of British colonial history.

Their experience of British colonialism led them to reject that history in a struggle for independence. That struggle for independence was premised on the irrelevance of Singapore's history as a British colony in the creation of a new future. The People's Action Party's (PAP) vision of Singapore's future in merger with Malaysia won that competition for Singapore's future and became the basis of a new historical narrative.

Hence the narrative of Singapore's past from British crown colony to merger with Malaya had to be discarded in 1965. A post-1965 generation had to reject the history of Singapore as a staple port dependent upon the peninsula for its hinterland. A new history of Singapore as a city-state capable of surviving on its own, without a hinterland, had to be developed.

To be sure, students of history still learnt about Singapore's colonial past and its links to the Malaysian peninsula from textbooks. But the larger national narrative emphasised Singapore's destiny as an individual sovereign state.

By the early 1980s, a new historical narrative of progress and modernisation through economic development was constructed.

It is a narrative which reduced and marginalised the narrative of political challenges and alternatives to the PAP's political dominance and drive for economic development in partnership with global capital.

Today a post-Cold War generation is questioning the logic and consequences of this technocratic and meritocratic pragmatism driving Singapore's economic drive to now become a global city networked with other global cities and with London, New York and Tokyo as its major nodes. This generation is concerned about the impact of this logic of driving for global city status on their own lives.

The post-independence generation born in the late 1960s to 1970s grew up accepting the history of Singapore as a vulnerable city-state as their home which they had to defend.

They are now joined by an even younger generation born after the Cold War, who take Singapore's sovereignty for granted and do not necessarily buy into the idea of Singapore's vulnerability. Serving national service has convinced them that the SAF is indeed a formidable armed force quite capable of defending Singapore, but the accompanying National Education narration of Singapore's history has not convinced many, who see the nation's fragility as "propaganda".

They are also now coming of age and demanding a say in the affairs of this city-state they consider their home. For if Singapore is indeed "my home" rather than a hotel, then should I not have a say in how the furniture in my home is arranged, and not defer to family elders?

Underlying the public discussion over Housing Board plans for the rejuvenation of Dawson Estate are issues of social memories of community and local identity. The controversy over the old cemetery at Bukit Brown is about a variety of civil society groups questioning the pragmatism of the view that the resting places of the dead must give way to housing for the living.

Another cycle of rewriting Singapore's history may be in the offing. It appears to be a rewriting that emphasises the local and social dimension of our past over the national and its global links.

A place for the little man

TO BE sure, attempts to bring the social aspects of Singapore's history to the fore are not entirely new. In 1923, Song Ong Siang published One Hundred Years' History Of The Chinese In Singapore. More recently, there was in 1986 James Francis Warren's Rickshaw Coolie: A People's History Of Singapore 1880-1940.

For too long the history of Singapore has been written as a history of great men and their times. But we need to also give a place in time to the little man (and woman) who built the kampung and places that define Singapore, as Brenda Yeoh and Lily Kong attempted in their edition of Portraits Of Places in 1995 or Chan Kwok Bun and Tong Chee Kiong did in their 2003 Past Times: A Social History Of Singapore.

The IPS survey suggests that it may be social memories of how local events, such as the MRT breakdowns of 2011, affected us as citizens that will loom large in the emerging rewriting of our history. The emerging issues in the rewriting of our history may be about how our sense of identity rooted in the places we went to school or in our HDB estate are uprooted when our old schools are relocated or the estate is rejuvenated.

The IPS survey also shows low awareness of the formation of the Monetary Authority of Singapore in 1970 and introduction of the Singapore currency in 1967.

This suggests low interest in the national narrative of Singapore as a city-state transforming into a global city challenged by a series of global and geopolitical upheavals. That may be due to the success of the old narrative of the PAP as a constitutionally elected government which can be trusted to deliver the public goods it promised.

Not all young Singaporeans are uninterested in national or political history. When they do take it up, however, the lens through which young historians interpret the past may differ from that used by older historians. A group of young historians are re-examining the justification for Operation Coldstore as a challenge to this narrative of the constitutionality of Singapore's political process. But their efforts have not increased awareness of Operation Coldstore in the larger population.

Ironically, it may be the prevailing success story of Singapore - a stable political system staffed by a meritocratic and technocratic PAP government to ensure the continuous provision of public goods - that may explain the low awareness of Operation Coldstore, the 1987 Marxist Conspiracy and the 1961 split of the PAP. These events may have sunk into the national consciousness as non-issues which can be forgotten.

The issue in a new cycle of rewriting of Singapore history is less about how to reiterate and enhance awareness of key political events in the old national narrative of Singapore as a city-state, but more about how to link the emerging concerns about the social memories of our rapidly changing identities as Singaporeans, with the national narrative of Singapore transforming from city-state to global city.

The writer is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and a co-author of Singapore: A 700-Year History.

The writer is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and a co-author of Singapore: A 700-Year History.

No comments:

Post a Comment